All cases are archived on our website. To view them sorted by case number, diagnosis or subspecialty, visit our main Case of the Week page. To subscribe or unsubscribe to Case of the Week or our other email lists, click here.

Thanks to Dr. K.V. Vinu Balraam, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra (India) for contributing this case and Dr. Akira Yoshikawa, Kameda Medical Center, Kamogawa City, Chiba (Japan) for writing the discussion. To contribute a Case of the Week, first make sure that we are currently accepting cases, then follow the guidelines on our main Case of the Week page.

Department of Health and Human Services

National Institutes of Health

NIH Clinical Center

Physician, Microbiology Service, Department of Laboratory Medicine

BETHESDA, MARYLAND (USA).

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) invites candidates with a strong Clinical Microbiology background, scientific leadership, and managerial credentials to apply for a Clinical Microbiologist position in the Department of Laboratory Medicine, NIH Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD.

The Clinical Center's Microbiology Service provides state-of-the-art diagnostic and consultation services, supports the clinical research programs, and conducts research in the field of microbiology. The Service consists of six sections: Bacteriology, Mycobacteriology and Mycology, Specimen Processing, Molecular Diagnostics, Genomics, and Parasitology. The laboratory has increasingly focused on molecular and NGS technologies and has been a pioneer in the development of innovative infectious disease diagnostics. In addition, we have an American Society for Microbiology CPEP-approved program in Medical and Public Health Laboratory Microbiology. The Microbiology service currently consists of 42 staff members including the Chief of Microbiology, three senior doctoral level microbiologists, and nine doctoral level scientists and post-doctoral fellows.

Candidates must have an MD with board certification/eligibility in either Clinical Pathology or Infectious Disease, as well as, a current, active, full, and unrestricted license or registration as a Physician from a State, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, or a territory of the United States. Certification in Medical Microbiology through the American Board of Pathology or through the American Board of Medical Microbiology is preferable, but not required. Salary will be commensurate with laboratory and managerial experience as well as scientific accomplishments.

A full Civil Service package of benefits (including retirement, health, life and long term care insurance, Thrift Savings Plan, etc.) is available for this position. Candidates for the position must apply online at www.usajobs.gov between 7/31/2018 and 8/9/2018, job announcement # 10247419. If you have questions about this position, please contact Alex Trader, HR Specialist, NIH at 301-435-4763 or at alex.trader@nih.gov. This position is subject to background investigation.

The Department of Health and Human Services and NIH are equal opportunity employers committed to equity, diversity and inclusion.

[10 July 2018, #7391]

Advertisement

Website news:

(1) Do you have a slide collection sitting on the shelf, waiting for you to have the time to do something with it? We don't want your work to go to waste, and so are creating a Gallery section for images at PathologyOutlines.com. If you have 500+ high quality digital images with diagnoses and captions, we will create a separate page(s) for them with your biography and picture. More...

(2) When you visit our Books page, you can search by date, publisher, series or subspecialty. Below subspecialty, there is a Search box for you to also search by title or author. Many users didn't realize this great function. Let us know if you cannot find a recently published Pathology book and we will be more than happy to add it.

(3) We now have a static menu bar so that the top of the header with the search box remains in place even if you scroll down on the page. Thanks to the pathologist who suggested this feature.

Visit and follow our Blog to see recent updates to the website.

Case of the Week #459

Clinical history:

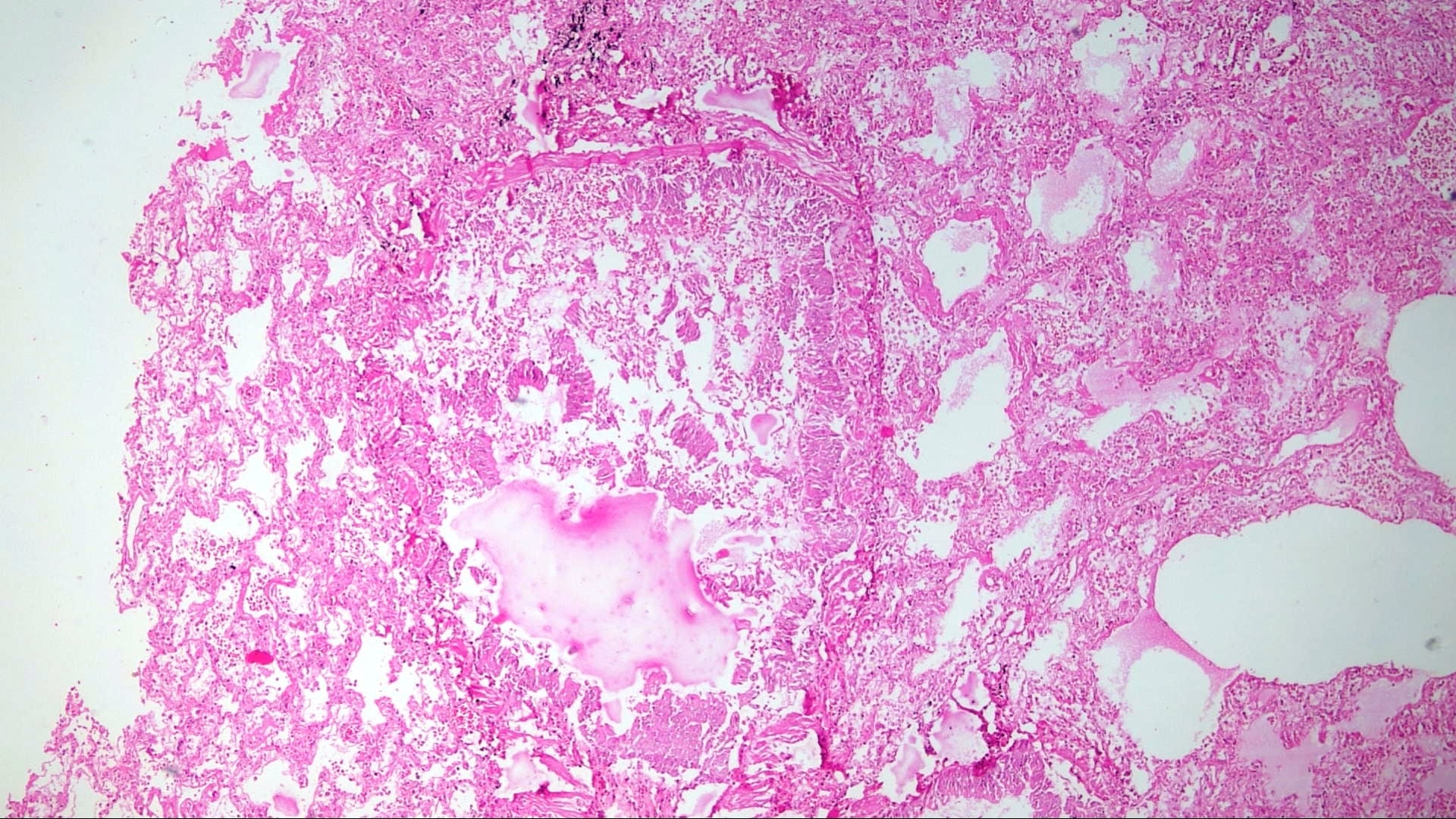

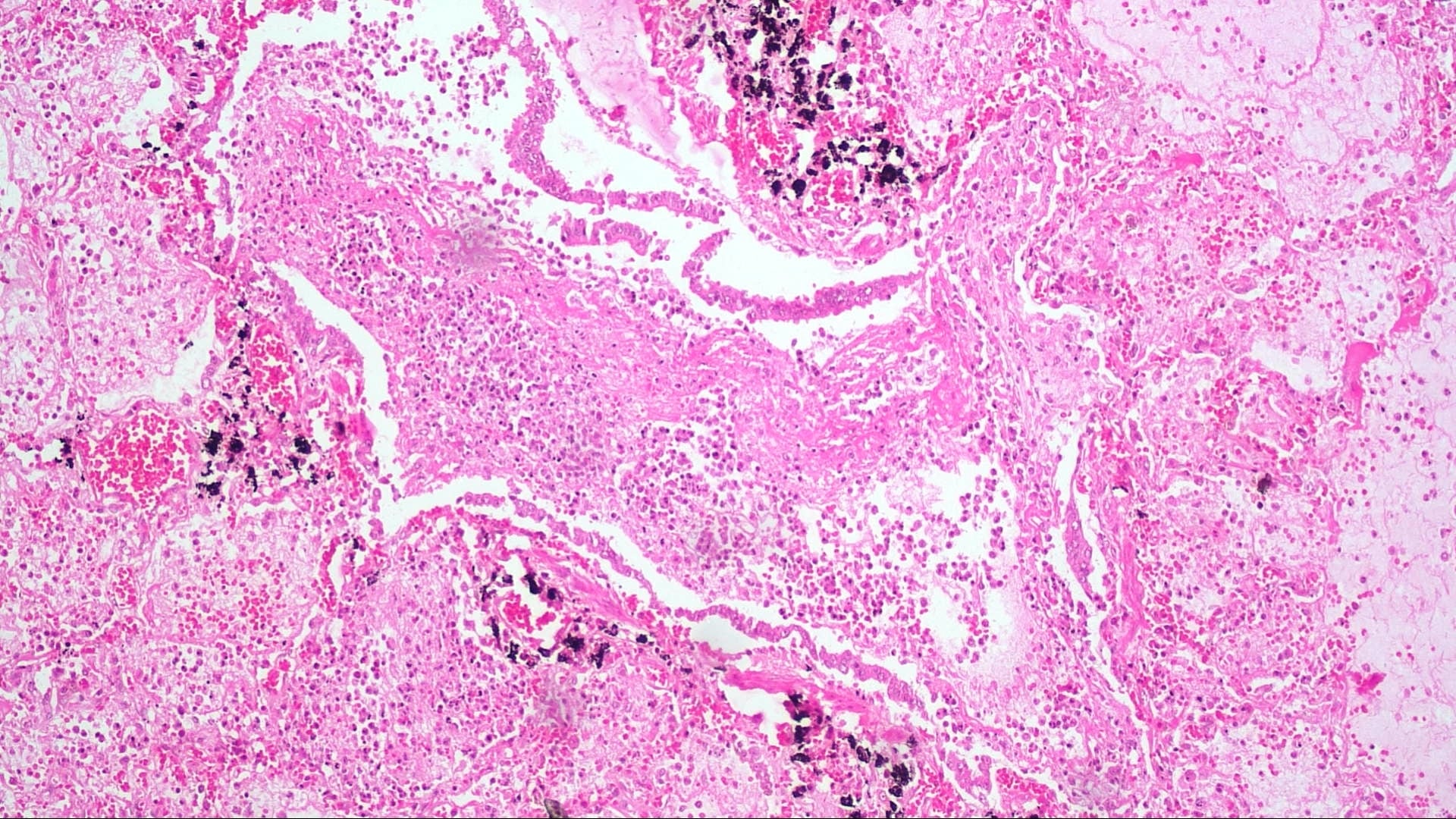

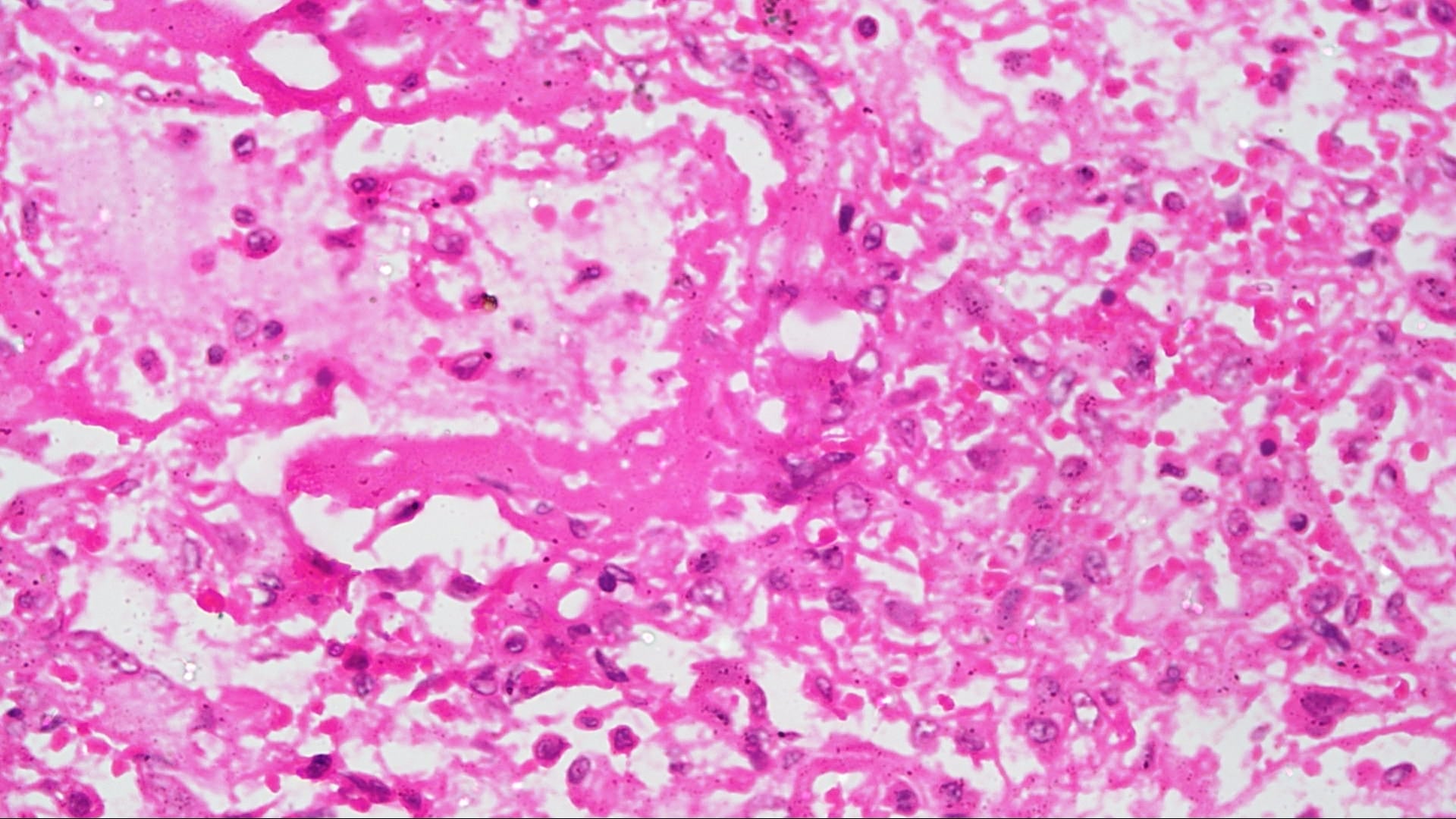

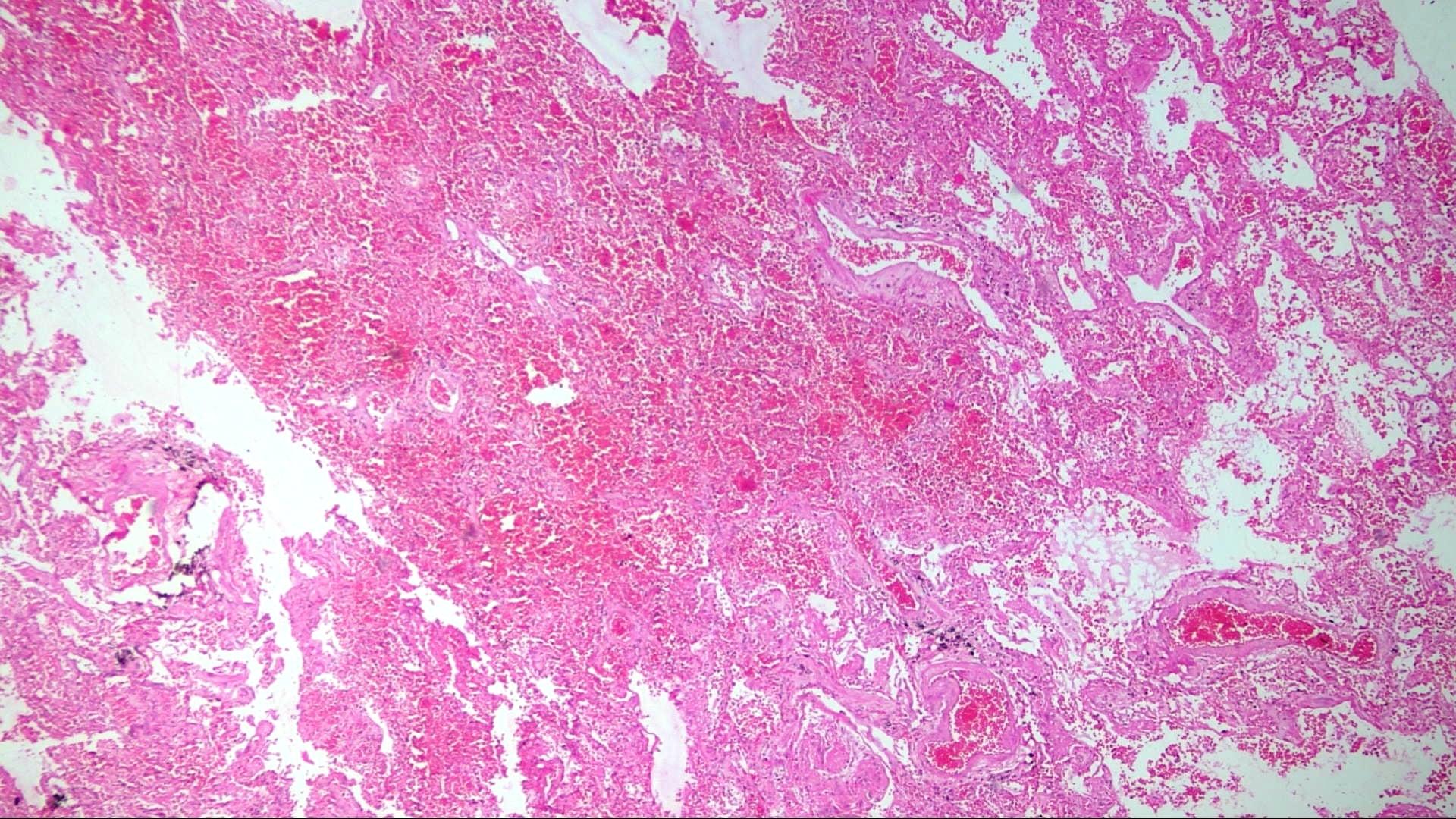

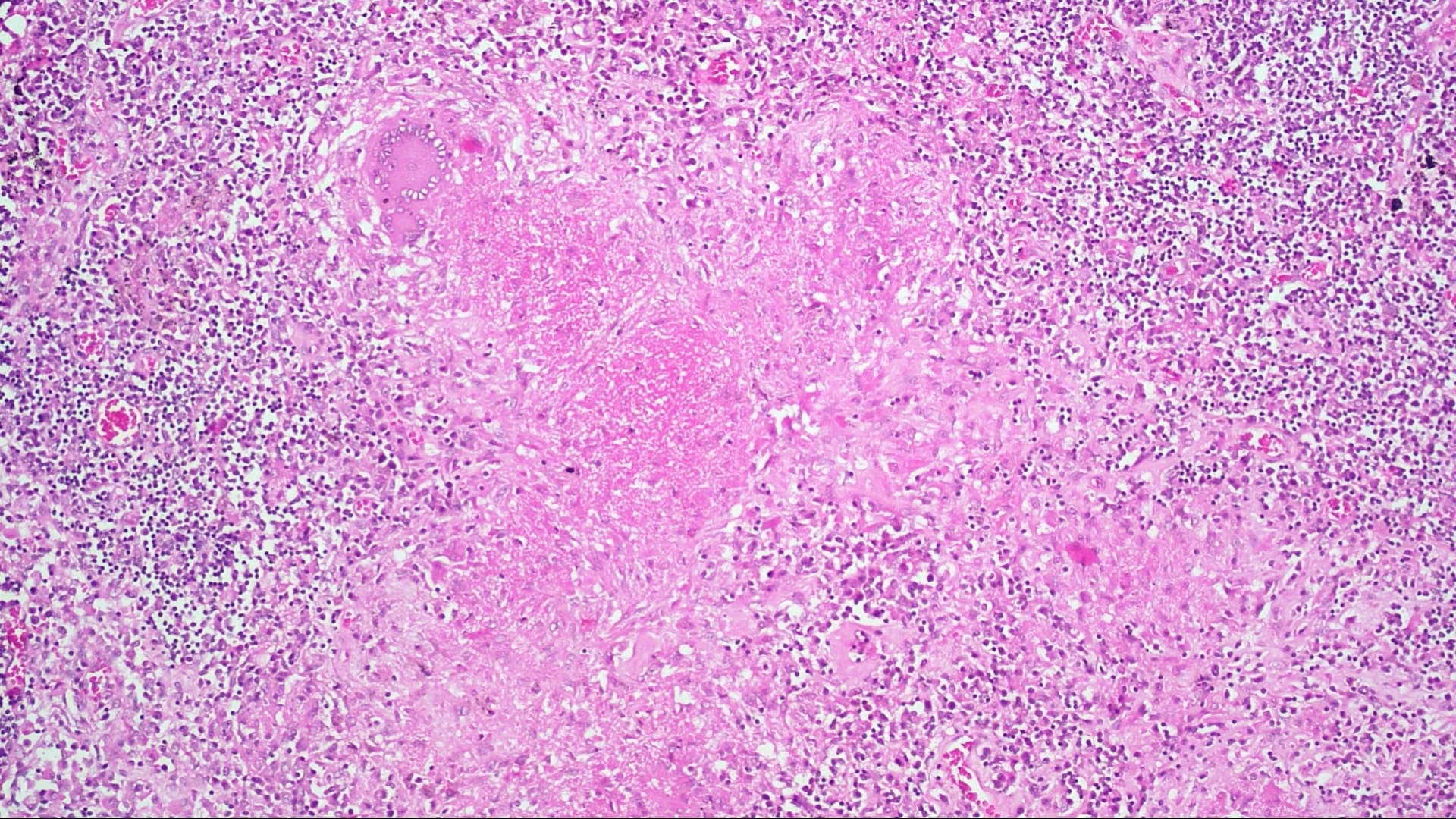

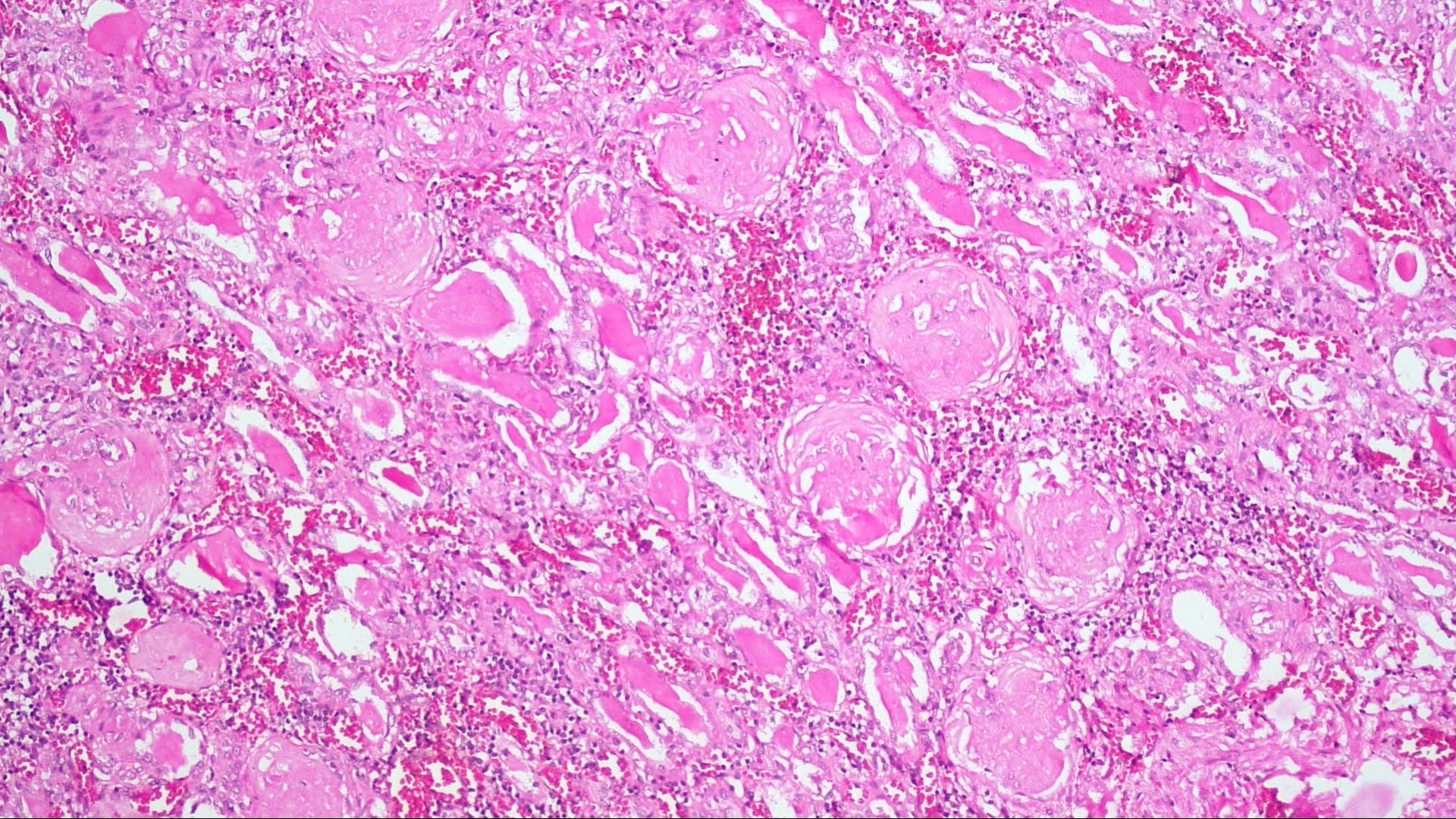

A 43 year old man in India with a prior history of alcohol abuse presented with fever for 3 days and sudden onset of shortness of breath. His SpO2 (blood oxygen saturation) was 80% on room air. Chest xray showed bilateral pneumonitis. He was intubated and given antibiotics but deteriorated and expired. These images are from the autopsy.

Histopathology images:

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis:

Consistent with H1N1 pneumonitis with diffuse alveolar damage

Test question (answer at the end):

Which histological feature is highly specific to influenza A/H1N1 infection in diffuse alveolar damage?

A. Neutrophilic aggregation

B. Organizing pneumonia

C. Alveolar hemorrhage

D. All of the above

E. None of the above

Discussion:

Autopsy found major histopathological changes in the lungs of septal inflammation, congestion and alveolar septal thickening along with features of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), i.e. diffuse intra-alveolar hemorrhage, reactive hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes and hyaline membrane formation. There was desquamating bronchitis in the form of epithelial ulceration along with plugging of the lumen with necro-inflammatory slough and submucosal inflammatory infiltrates. In addition, caseating epithelioid granulomas were found in the pre-tracheal and pre-carinal lymph nodes. Another major target organ was kidney, where end stage renal disease was histologically manifested by glomerulosclerosis, thyroidization of tubules and lymphocytic interstitial infiltrate. A nasopharyngeal swab was positive for H1N1 virus by RT-PCR. Ziehl–Neelsen stain was negative for acid fast bacilli. The final autopsy diagnosis was “features consistent with H1N1 pneumonitis, most likely superimposed on caseating granulomatous lymphadenitis”.

Influenza A/H1N1 is one of the most common subtypes of seasonal influenza and has provoked historical global pandemics. The 1918-1919 H1N1 influenza pandemic ("Spanish influenza") was among the most deadly events in recorded human history, killing an estimated 50 million - 100 million people (J Infect Dis 2007;195:1018). In March to April 2009, another outbreak of influenza A/H1N1 began in Mexico and spread to North America and across the world (Clin Infect Dis 2011;52 Suppl 1:S75). Vaccination effectiveness is high for both seasonal and pandemic subtypes of influenza A/H1N1 (Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:942).

Clinical characteristics of influenza A/H1N1 are similar to other types of influenza (N Engl J Med 2010;362:1708). Influenza A/H1N1 is transmitted person to person through sneezing and coughing via respiratory droplets. The incubation period is 1.5-3 days. Patients often present with influenza-like symptoms of fever, cough and myalgia. Rapid influenza diagnostic testing is useful, with moderate sensitivity and high specificity, but does not differentiate among influenza A variants (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests). The CDC recommends antiviral treatment as early as possible for patients who are hospitalized; have severe, complicated or progressive illness; or who are at higher risk for complications including children, the elderly and those with chronic respiratory disease) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Influenza Antiviral Medications - Summary for Clinicians).

Although influenza A/H1N1 is usually self-limited, some cases present with a severe respiratory disorder including hemorrhagic bronchitis / bronchiolitis, pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (Am J Pathol 2015;185:1528, Annu Rev Pathol 2008;3:499). DAD is the most consistent histologic lung pattern in fatal cases (Am J Pathol 2010;177:166, Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:235).

DAD is the pathological hallmark of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). It is characterized by hyaline membrane and intra-alveolar edema and hemorrhage in the exudative (acute) phase, proliferation of fibroblasts and type II pneumocytes in the proliferative (subacute) phase and dense fibrosis and architectural distortion in the fibrotic (chronic) phase (Am J Pathol 1976;85:209, Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:719, Clin Chest Med 2000;21:435, N Engl J Med 2000;342:1334). ARDS / DAD is caused by various pulmonary and extrapulmonary etiologies, and removal of the original insult is the key to treatment. Therefore, clinical and systemic examination for cause of origin is necessary. If the patient is suspected of having ARDS / DAD associated with influenza infection, real time RT-PCR of lung tissue is useful due to its high sensitivity and specificity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Information on Rapid Molecular Assays, RT-PCR, and other Molecular Assays for Diagnosis of Influenza Virus Infection). Since secondary bacterial pneumonia, especially due to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia and Staphylococcus pyogenes coexist with 20% of severe influenza infections, bacterial culture, gram stains and Giemsa stains are recommended (N Engl J Med 2010;362:1708).

This case has coexisting caseating granulomatous lymphadenitis. In a high prevalence country such as India, caseating granulomatous lymphadenitis suggests Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection as the first differential, followed by non tuberculous mycobacteria (Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases 2017;7;1). A negative ZN stain does not exclude mycobacterial infection due to its low sensitivity (20-80%); PCR and light emitting diode fluorescence microscopy are more sensitive (Cohen et al: Infectious Diseases, 4th Edition, 2016, Eur Respir J 2016;47:929). Progressing pulmonary tuberculosis causes immunosuppression, which may have contributed to the rapid and fatal course of H1N1 infection in this patient.

Test Question Answer:

E. No histological finding specific to influenza infection has been identified. The findings in A, B and C are quite common in diffuse alveolar damage of any etiology.