Table of Contents

Definition / general | Essential features | Epidemiology | Sites | Pathophysiology | Clinical features | Diagnosis | Case reports | Treatment | Gross description | Microscopic (histologic) description | Microscopic (histologic) images | Cytology images | Differential diagnosis | Additional referencesCite this page: Weisenberg E. Strongyloides stercoralis. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/colonstrongyloides.html. Accessed August 22nd, 2025.

Definition / general

- Infection of the colon by the intestinal nematode Strongyloides stercoralis

Essential features

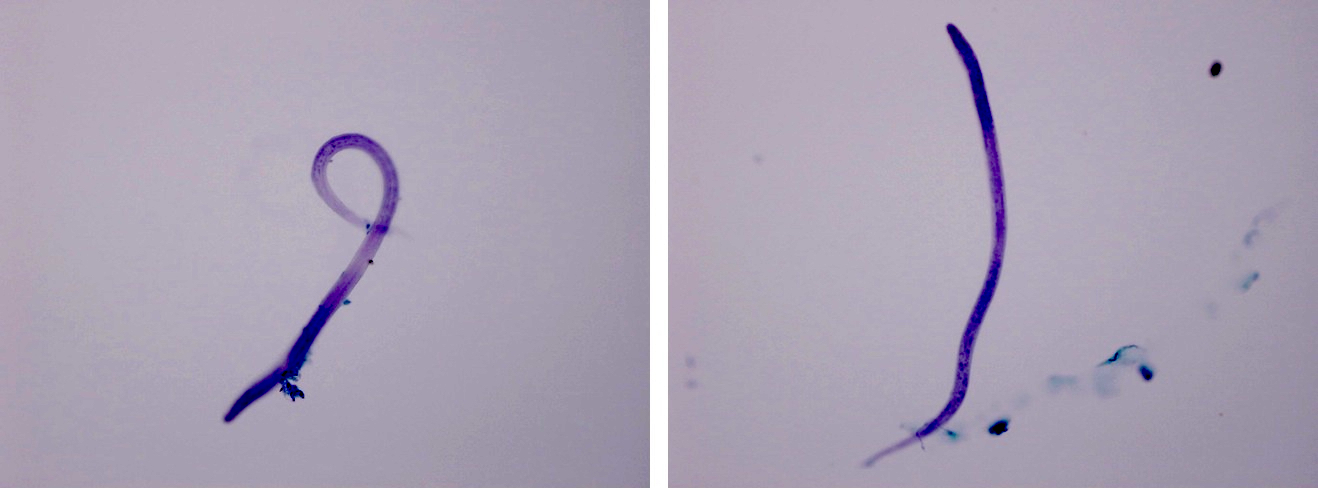

- Strongyloides filariform larvae in fecally contaminated ground penetrate skin, enter the systemic circulation and migrate to the lungs where they induce inflammation

- They climb the tracheobronchial tree and are swallowed

- In the intestines they mature into adult worms

- Eggs (made by mature worms) hatch in the intestines and release rhabditiform larvae that are excreted

- Intestinal infection may be asymptomatic or be associated with diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, malabsorption or other symptoms

- Infection usually occurs in the small intestine but may occur in the stomach, colon or rarely elsewhere

- Rhabditiform larvae may change into filariform larvae that penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the circulation, leading to autoinfection that may cause severe tissue and peripheral eosinophilia and infection lasting decades

- Immunosuppressed patients may develop massive disseminated fatal infection from accelerated autoinfection

Epidemiology

- Strongyloides is found in all continents except Antarctica, but is most prevalent in warm and rainy parts of the tropics and subtropics

- Worldwide estimates vary from 30 to 100 million infected people

- Infection is more common in adults

- In the United States, endemic regions include southeastern urban areas with large immigrant populations, mental institutions and Appalachia

- Immigrants and military veterans who have served in endemic regions may harbor the parasite for up to 60 years

- Worldwide, immigrants and refugees are more likely to be infected; endemic areas of southern and central Europe also exist

- Transmission has been documented from close personal contact and from men who have sex with men

Sites

- Infection usually occurs in the lung and small intestine

- The stomach, colon, appendix and liver may also be affected

- Involvement of the central nervous system may occur with disseminated disease

- Esophageal disease is rare

Pathophysiology

- Strongyloides filariform larvae in fecally contaminated ground penetrate skin, enter the systemic circulation and migrate to the lungs where they induce inflammation

- They climb the tracheobronchial tree and are swallowed

- In the intestines they mature into adult worms

- Eggs (made by mature worms) hatch in the intestines and release rhabditiform larvae that are excreted

- Rhabditiform larvae may change into filariform larvae that penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the circulation, leading to autoinfection

- Free living adult male and female worms may be found in soil; they mate and produce rhabditiform larvae that may become infective filariform larvae

Clinical features

- Migration of larvae through the lungs may be associated with wheezing, migratory pneumonia or cough

- Involvement of the intestines may be asymptomatic but may be associated with abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, malabsorption, nausea, GI bleeding or vomiting

- Involvement of the appendix may cause acute appendicitis

- Immunosuppressed patients are at risk of disseminated disease, especially those receiving corticosteroids, chronically ill and hospitalized, or with HTLV I infection

- Those with disseminated disease may lack peripheral eosinophilia

- Untreated disseminated infection is essentially 100% fatal and even with treatment up to 25% of patients will die

- Interestingly, patients with HIV/AIDS are not at high risk for disseminated infection

Diagnosis

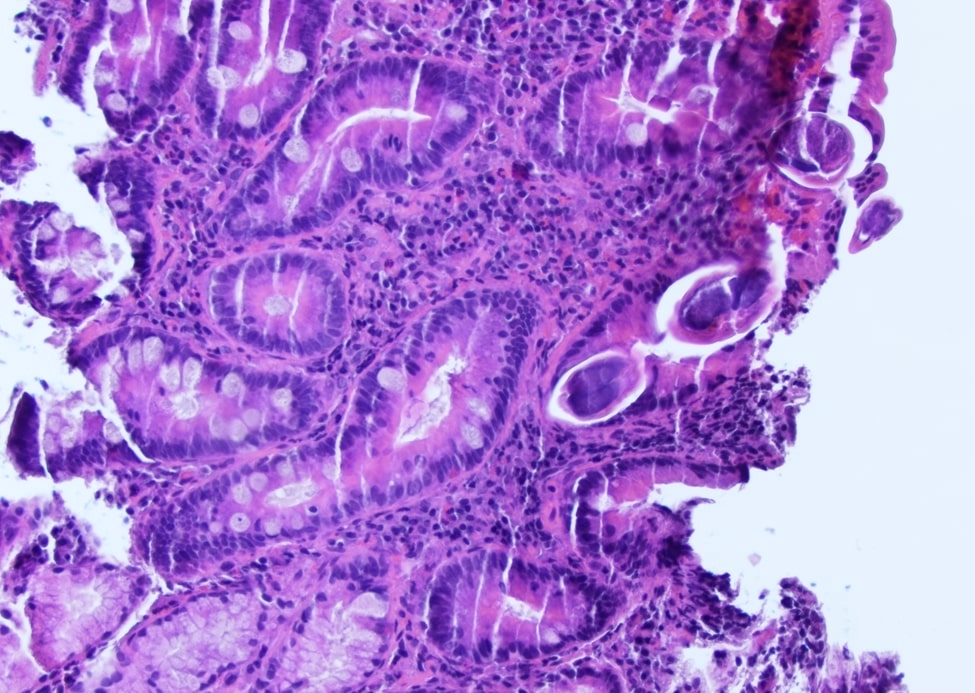

- In biopsy specimens, larvae and adult worms are identified within crypts

- If the diagnosis is suspected or confirmation is necessary, stool ova and parasite examination and serologic testing is available

- Ova and parasite testing is not highly sensitive and multiple examinations may be necessary to detect the parasite

- PCR testing of stool is extremely sensitive and specific

Case reports

- 41 year old man with worm infection mimicking inflammatory bowel disease (Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2015 Dec 4 [Epub ahead of print])

- 66 year old male with colonic pseudopolyposis and gastrointestinal bleeding (Surg Endosc 1987;1:175)

- 67 year old nonimmunocompromised man with diarrhea, weight loss and microcytic anemia (J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;28:77)

- 68 year old woman with coexisting rheumatoid arthritis (Ann Clin Microbiol 2010;9:27)

Treatment

- Infection should always be treated

- Ivermectin is the first line treatment in most cases

- Albendazole or thiabendazole are other options

- Disseminated disease should be treated with prompt antihelmintic therapy, broad spectrum antibiotics and decrease of immunosuppression if possible

Gross description

- Endoscopy may show small ulcers or hyperplastic mucosa

- Adult female worms approximately 2 mm in length may be seen

- The mucosa may resemble pseudomembranous colitis

- Fulminant infection may appear similar to idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease

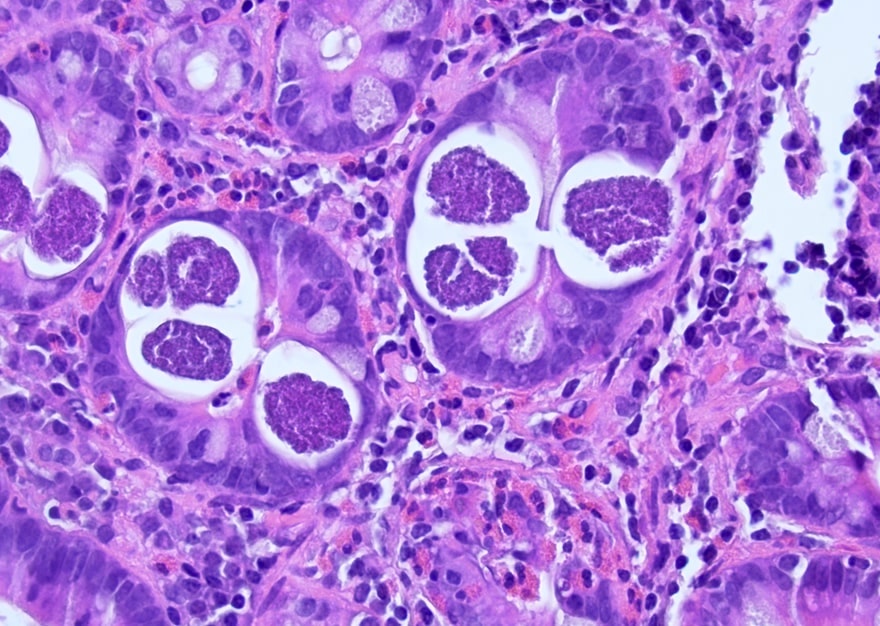

Microscopic (histologic) description

- Tissue eosinophilia and granulocytic infiltration that may cause abscess formation are present

- Adult worms or larvae may be found within crypts

- Necrosis or granulomas may be present

- Ulcers with fissuring similar to Crohn’s disease may occur

Microscopic (histologic) images

Differential diagnosis

- Capillaria, Trichuris trichuria and other infections, especially other nematodes, pseudomembranous colitis, inflammatory bowel disease