Table of Contents

Definition / general | Acidophil body | Ballooning (feathery) degeneration | Bile ductules | Bridging necrosis | Centrilobular necrosis | Giant cell transformation | Glycogen nuclei | Interface hepatitis | Interlobular bile duct | Mallory hyaline | Macrovesicular steatosis | Microvesicular steatosis | Passive congestion | Submassive necrosis | Additional references | Board review style question #1 | Board review style answer #1 | Board review style question #2 | Board review style answer #2Cite this page: Patel KS, Windon AL. Forms of hepatic injury. PathologyOutlines.com website. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/liverpatternshepaticinjury.html. Accessed May 12th, 2024.

Definition / general

- This broad topic highlights the pathophysiology, microscopic findings and associated hepatic diseases with commonly encountered structural changes, patterns of cell damage and necrosis, intracellular hepatic changes and common patterns of biliary reaction to injury in hepatology

Acidophil body

- Active form of programmed cell death, resulting in hepatocyte shrinkage, nuclear chromatin condensation (pyknosis) and fragmentation (karyorrhexis)

- Also called Councilman body, single cell death, apoptotic body

- Councilman bodies are essentially synonymous with acidophil bodies and were described as hepatocyte necrosis in the pathology of yellow fever; some pathologists prefer to restrict this term to the context of yellow fever

- Pathophysiologically and biochemically, cells undergoing apoptosis exhibit externalization of phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of plasma membrane, increased mitochondrial membrane permeability and release of proteins from the intermembrane space with activation of caspases and endonucleases, resulting in cleavage of structural proteins and DNA

- Usually a nonspecific finding to describe a dead hepatocyte, most commonly seen in major inflammatory hepatic diseases: viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, drug induced liver injury and low grade / transient ischemia

- Microscopically identified as smaller, shrunken, more eosinophilic round body generally lacking a nucleus or with a small shriveled nucleus, with or without accompanying inflammation

- Spotty necrosis is used to describe necrosis of minute clusters of hepatocytes with scattered acidophil bodies, usually in association with lymphocytic inflammation

- Focal necrosis refers to necrosis involving larger groups of hepatocytes within a lobule, usually associated with scattered acidophil bodies

- References: Liver Int 2004;24:85, Hepatology 2004;39:273, Histopathology 1983;7:195

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

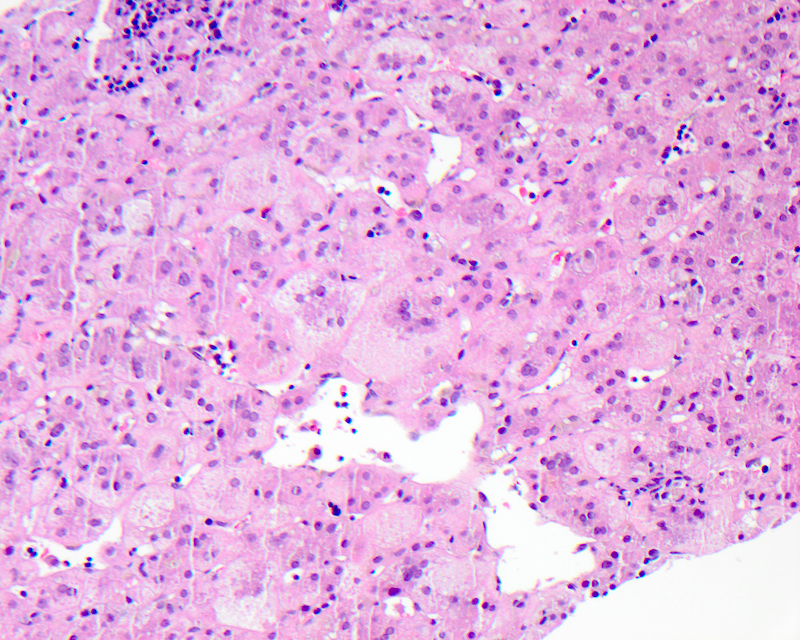

Ballooning (feathery) degeneration

- Term used to describe swelling and rounding up of injured hepatocytes in the setting of marked hepatitis or cholestasis; considered a sign of progression to hepatocyte apoptosis and cell death

- Also called feathery degeneration in the setting of chronic cholestasis

- Pathophysiologically, ballooning is a result of severe cell injury, depletion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and rise in intracellular calcium, leading to loss of plasma membrane volume control and disruption of the hepatocyte intermediate filament network

- Commonly seen in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and cholestatic liver disease but can also be seen in viral hepatitis and certain drug induced liver injury

- Grossly, liver may be transformed into swollen and turgid organ, exhibiting pallor

- Microscopically:

- Can be identified at low power as hepatocytes 2 - 3 times the size of normal adjacent hepatocytes

- Ballooned cells lose their usual polygonal shape and become rounded with watery edematous wispy rarified cytoplasm that is less eosinophilic than the neighboring cells with vacuolization and lacking fat accumulation

- These cells demonstrate clumping of intermediate filaments, characterized as strands of eosinophilic, ropey cytoplasmic material (see Mallory hyaline below)

- Feathery degeneration specifically refers to pale, swollen, injured hepatocytes in a periportal or periseptal (edge of cirrhotic nodule) distribution in livers with chronic cholestasis due to retention of bile salts

- Cholate stasis is synonymous with feathery degeneration

- Negative immunohistochemical stains: absent or decreased cytoplasmic immunostaining for intermediate filament by cytokeratin 8 and cytokeratin 18

- Reference: J Hepatol 2008;48:821

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

Bile ductules

- Bile ductules are small epithelial tubular structures at the periphery of the portal tracts, lined by 4 to 5 small cuboidal cholangiocytes and usually traversing the portal tract mesenchyme between terminal bile ducts and canals of Hering

- Also referred to as cholangioles

- Cells of origin for bile ductules are postulated to be hepatic progenitor stem cells and metaplastic hepatocytes

- Microscopically, bile ductules are distinctly different from bile ducts, which are tubular structures located in the central region of the portal tract, usually accompanied by a similarly sized hepatic artery

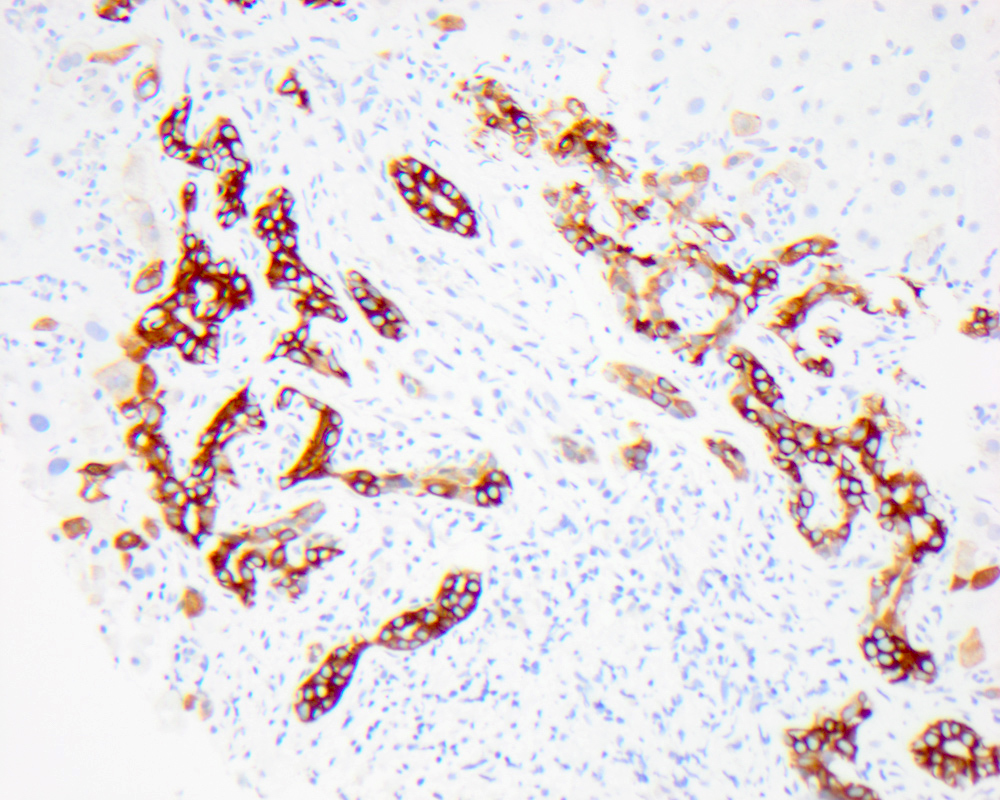

- Bile ductular proliferation is the proliferation of small bile ductules at the periphery of the portal tract and can represent biliary obstruction when accompanied by neutrophils and portal edema or a pattern of liver injury (as ductules are a source of liver progenitor cells)

- Bile ductular reaction is used when the proliferating bile ductules are accompanied by neutrophils present in the stroma adjacent to the ductules (though many pathologists consider ductular proliferation and ductular reaction synonymous)

- Bile ductular reaction can be associated with biliary obstruction (type I), active hepatitis (type II) and massive liver necrosis (type III)

- Positive immunohistochemical stains: cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 19

- References: Hepatology 2019;69:420, Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15:259, Virchows Arch 2011;458:271, Mod Pathol 2004;17:874, Histopathology 2010;56:415

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

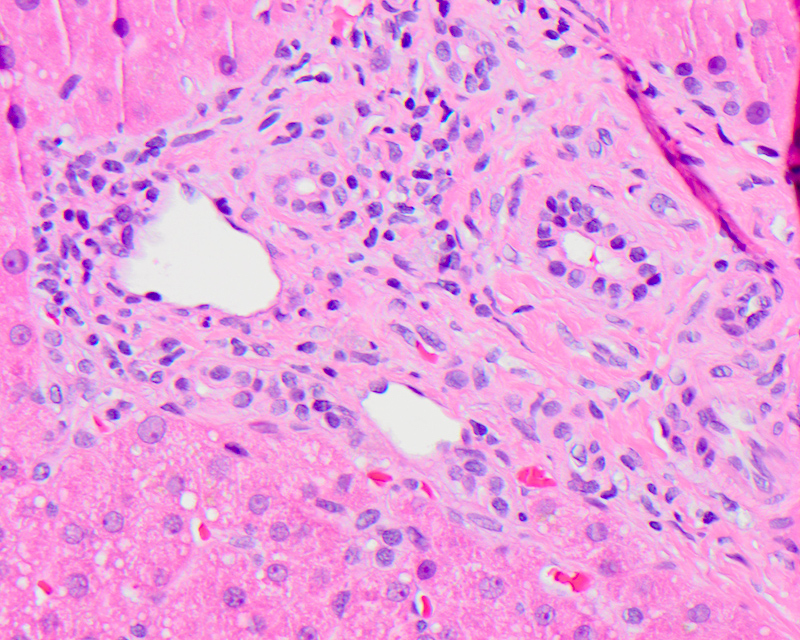

Bridging necrosis

- Necrosis is the predominant mode of death with onset of irreversible injury, in states of extreme ATP depletion (as during ischemia or hypoxic cell injury), toxic injury (as from acetaminophen) and oxidative stress with reactive oxygen species formation

- Pathophysiologically, necrosis is accompanied by extensive damage to all cellular membranes, swelling of lysosomes, vacuolization of mitochondria and extensive catabolism of cellular membranes, proteins, ATP and nucleic acid, with karyolysis and release of cellular contents

- Necrosis is a common denominator in acute and chronic liver diseases and it is usually followed by progressive fibrosis, with persistence of the underlying cause

- Multiple commonly identified patterns of necrosis: apoptosis / acidophil body (individual cell necrosis), spotty and focal necrosis, zonal necrosis, bridging necrosis, piecemeal necrosis (interface hepatitis), confluent necrosis (submassive and massive necrosis)

- Although the patterns of necrosis are not entirely specific, they can be important clues towards determining or confirming the underlying cause and severity of liver disease

- Bridging necrosis refers to septa of confluent necrosis (large area of hepatocyte necrosis with inflammation) bridging adjacent central veins of hepatic lobules and portal triads

- 3 main types: central - central (linking perivenular areas), central - portal (linking terminal hepatic venules to portal tracts) and portal - portal (linking portal tracts)

- Usually associated with severe acute viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, drug induced hepatitis (acetaminophen toxicity) or other toxin exposure

- Portal - portal bridging necrosis is common in conditions in which portal tracts are widened (e.g. chronic hepatitis or biliary tract disease)

- Central - central bridging necrosis is seen in parenchymal hypoperfusion and venous outflow obstruction

- Central - portal bridging necrosis is a fairly common feature of viral acute hepatitis and also seen in exacerbations of chronic hepatitis

- Connective tissue stains like Masson trichrome, elastin and reticulin are helpful in differentiating between bridging necrosis and bridging fibrosis; elastin fibers are found only in established septa but not in areas of recent parenchymal collapse and necrosis; trichrome stain shows some dull blue staining in the necrotic zones, representative of collapsing residual parenchymal framework; reticulin stain shows compression of the parenchymal framework in the necrotic zones

- References: Am J Dig Dis 1978;23:1076, N Engl J Med 1970;283:1063, Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2017;10:53, Acad Forensic Pathol 2018;8:256

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

Centrilobular necrosis

- Refers to a distribution of necrosis within the centrilobular tissue of the hepatic lobule around the central vein (acinar zone 3), most prone to ischemia and metabolic toxin injury

- Centrilobular zone (acinar zone 3) is especially vulnerable to ischemic injury due to anatomic location at the distal end of afferent blood flow

- Microscopically shows ischemic necrosis characterized by coagulative hepatocyte necrosis, pyknotic or karyorrhectic nuclei, sharply demarcated with apoptotic bodies at the interface of healthy and necrotic hepatocytes; sinusoidal dilation and congestion can be prominent if a component of right sided heart failure is present

- Usually associated with ischemia, drugs, venous outflow impairment, preservation / reperfusion injury, alcoholic hepatitis

- Another important cause is ischemia and static liver injury associated with circulatory failure or shock, severe venous outflow impairment, commonly seen at autopsy

- Needs to be distinguished from coagulative necrosis, where hepatocyte necrosis is away from the central vein

- Reference: Clin Liver Dis 2017;21:89, J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1993;8:530

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

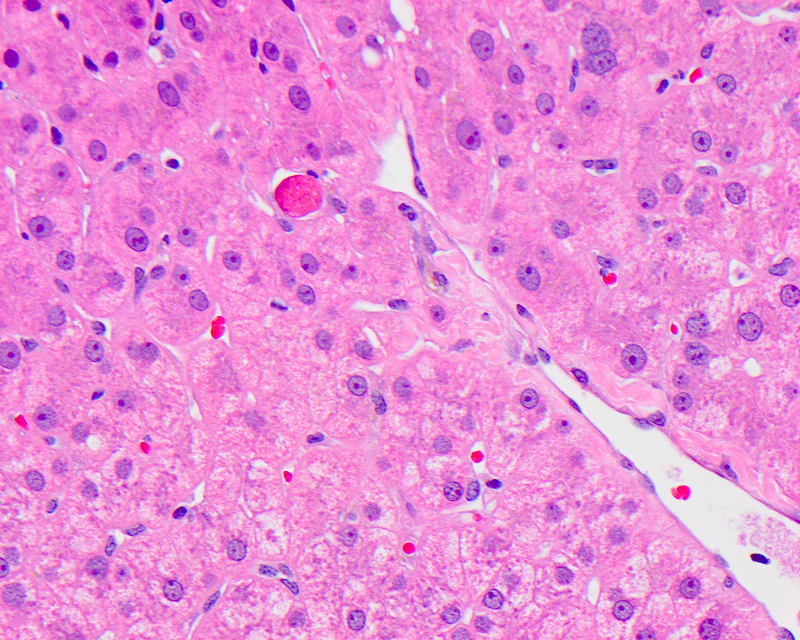

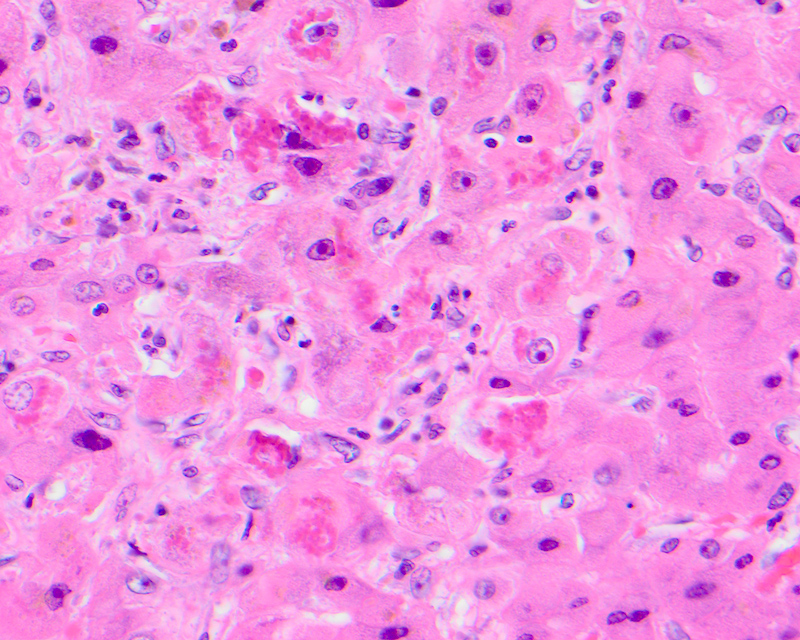

Giant cell transformation

- Defined as the coalescence of hepatocytes with 3 or more nuclei, with or without free floating canalicular or intracellular pigmented inclusions

- Can be nonspecific or a part of various neonatal and adult conditions

- Pathophysiologically, in adults it is thought to be due to the detergent action of retained bile salts, leading to dissolution of plasma membranes and coalescence of adjacent hepatocytes

- Seen as a part of adult giant cell hepatitis, also referred to as postinfantile giant cell hepatitis or syncytial giant cell hepatitis

- Commonly caused by a viral infectious etiology, like HHV6A, CMV, HEV and EBV; can be seen in autoimmune hepatitis, drugs, chronic cholestatic conditions, including primary biliary cholangitis, hepatitis C

- In neonates, it is postulated that giant cells result from mitotic inhibition of the growing liver by an injurious agent

- Seen in neonatal giant cell hepatitis and associated with neonatal cholestatic syndromes, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Niemann-Pick disease type C, bile salt export pump (BSEP) deficiency

- References: Ann Hepatol 2009;8:68, Hepat Res Treat 2013;2013:601290, J Clin Exp Hepatol 2016;6:244, Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1498

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

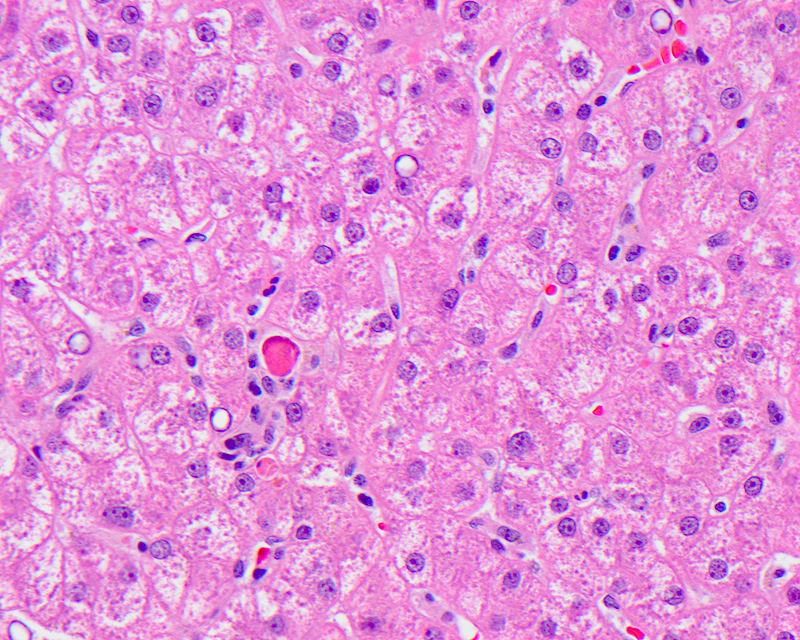

Glycogen nuclei

- Glycogenated nuclei are clear vacuoles that typically fill up most of the nuclei, leaving only a small rim of chromatin at the nuclear edges

- Found anywhere in the lobule but more common in zone 1 periportal hepatocytes

- Usually tend to cluster in small discrete patches but can be seen as single scattered hepatocytes

- Pathophysiologically the significance is unclear; some studies suggest they are indicative of hepatocyte senescence

- Commonly seen in diabetes, steatosis, pediatric liver disease, Wilson disease, some drugs, glycogenic hepatopathy

- References: World J Diabetes 2015;6:321, J Clin Pathol 2012;65:557

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

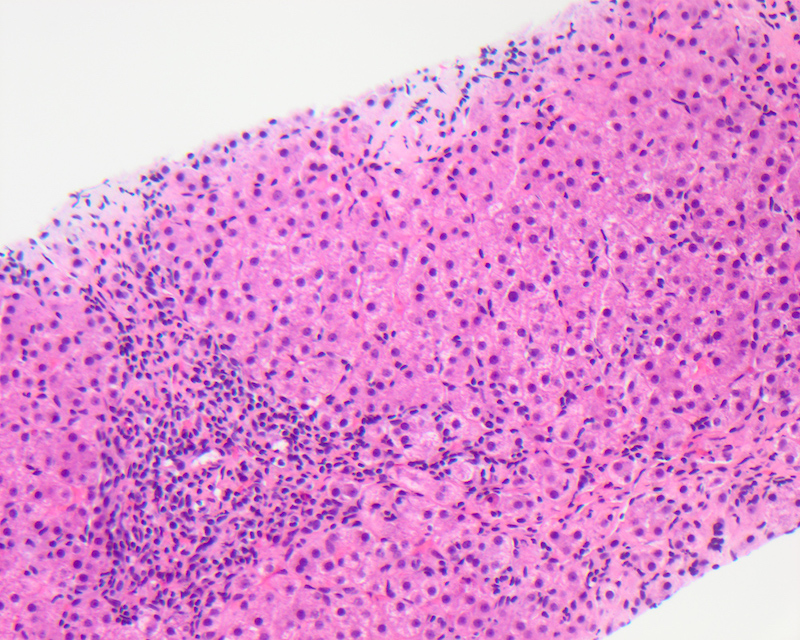

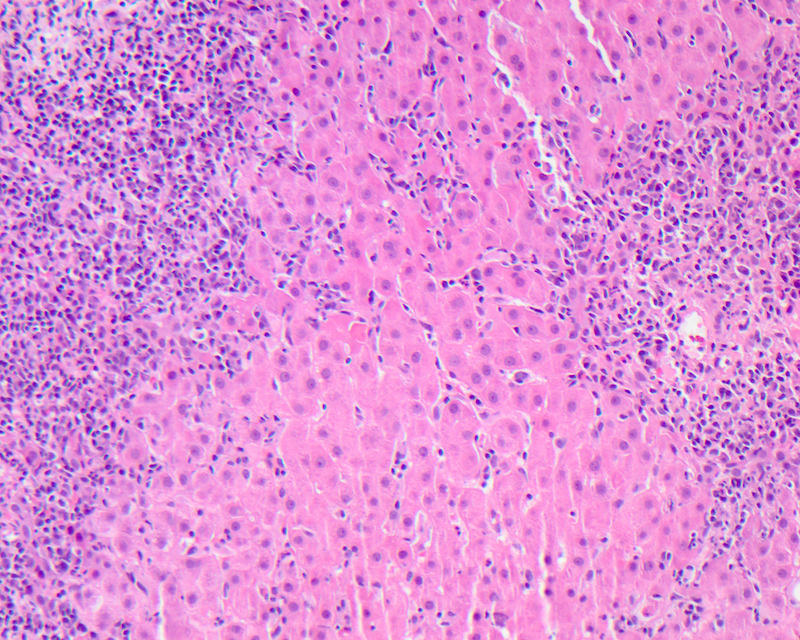

Interface hepatitis

- Defined as damage and progressive loss of hepatocytes at the interface of the lobular parenchyma and connective tissue / stroma of the portal zone, accompanied by a variable degree of inflammation and fibrosis

- Inflammatory infiltrate is composed mainly of lymphocytes, with or without plasma cells and can be accompanied by fibrosis of the affected areas with new formation of collagen and other extracellular matrix components

- Progressive interface hepatitis usually results in more severe fibrosis

- Also called as piecemeal necrosis, periportal hepatitis, interface activity, periportal activity

- Sometimes also referred to as classical or lymphocytic piecemeal necrosis in order to distinguish it from biliary, ductular and fibrotic piecemeal necrosis, which are found in chronic biliary tract disease

- Pathophysiologically, when liver injury occurs at the interface involving destruction of hepatocytes with an influx of inflammatory cells, the limiting plate (row of hepatocytes surround the portal tract) is compromised or destroyed, leading to proliferation of the canals of Hering and ductular compartment, giving rise to ductular reaction

- Formerly the defining feature of chronic active hepatitis due to viral causes; however, can be seen in acute and chronic hepatitis from other causes including autoimmune hepatitis

- Spillover is a term used for presence of an inflammatory infiltrate at the interface that does not damage the limiting plate

- References: Liver Transpl 2008;14:946, Exp Mol Pathol 2001;71:137

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

Interlobular bile duct

- Also called interlobular ductule

- Carries bile produced by hepatocytes which travels through an intralobular network of bile canaliculi, draining into the canal of Hering and then into bile ductules

- Usually a part of the interlobular portal triad, microscopically localized by looking for the larger portal tracts; however, they are inconsistently sampled in needle biopsy specimens

- Cells of the ducts are cuboidal epithelium, resting on a basement membrane, with increasing amount of connective tissue

- Common degenerative changes include cytoplasmic vacuolization, eosinophilic change, nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia

- Biliary epithelial swelling and atrophy, disordered nuclear polarity and sloughing can be seen in both inflammatory and neoplastic conditions

- Nuclear pyknosis, apoptosis, fading and uneven spacing usually anticipate duct loss and are seen in injured ducts as variably distorted ducts with irregularly shaped lumens

- Injury of the bile ducts is commonly seen with bile duct obstruction, chronic biliary disease or as a nonspecific reaction in any chronic liver disease

- Reference: Kaplowitz: Drug-Induced Liver Disease, 1st Edition, 2002

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

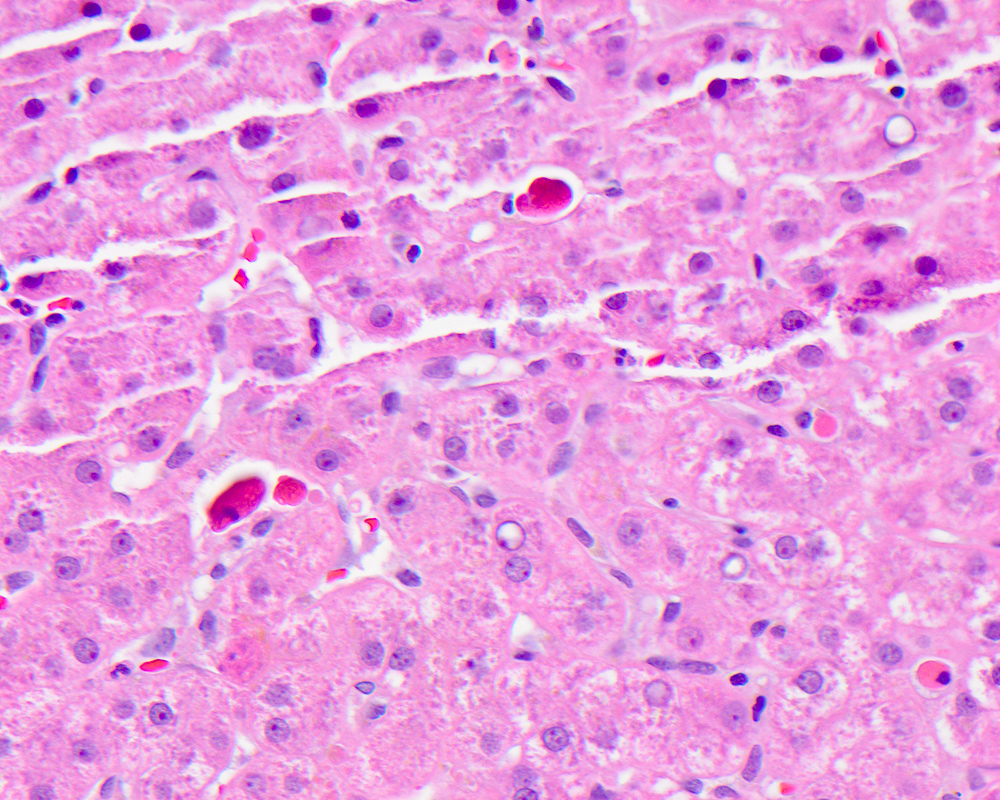

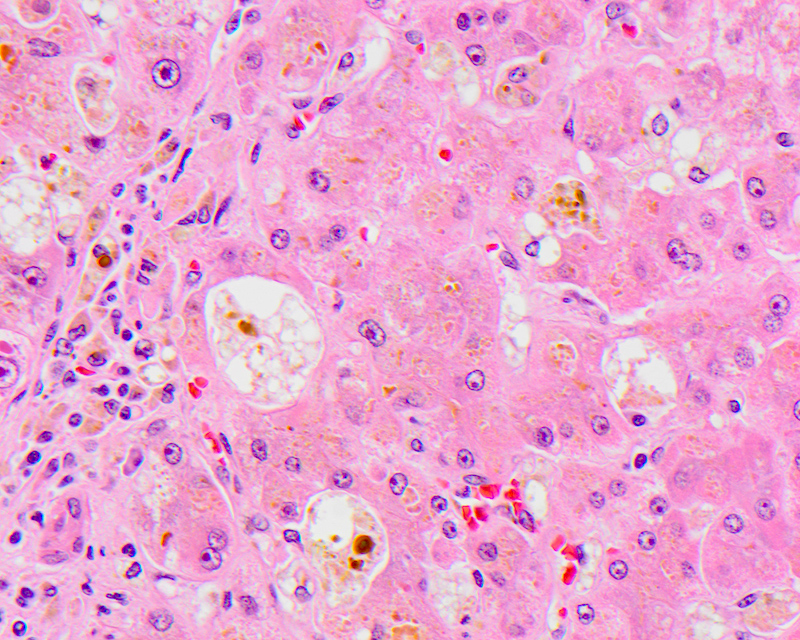

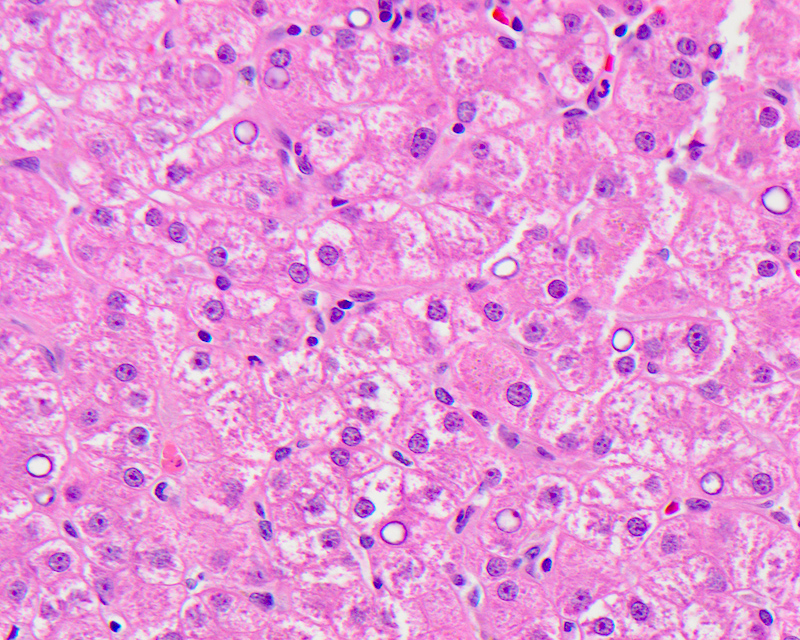

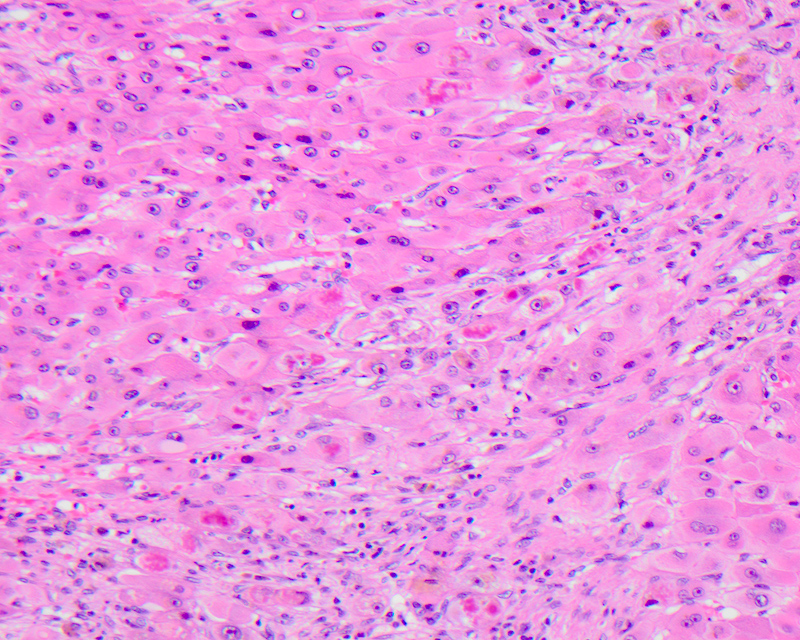

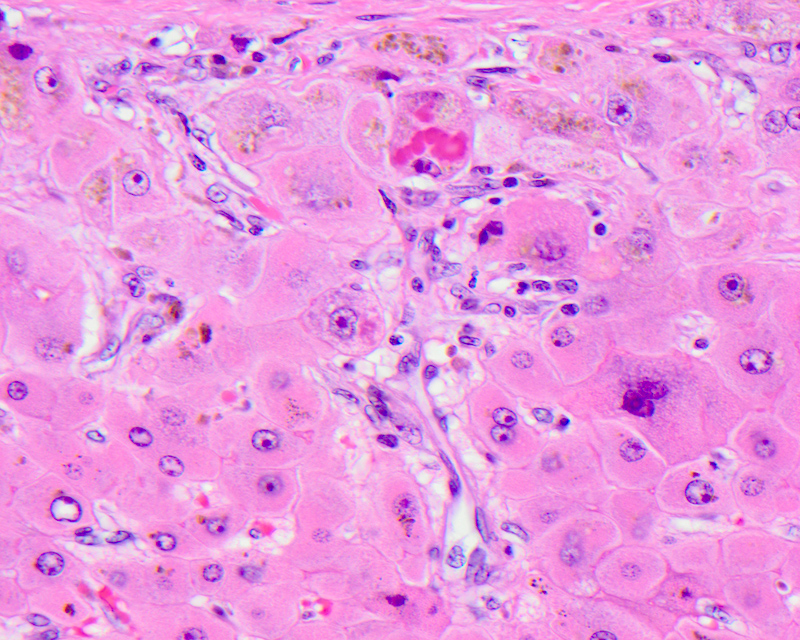

Mallory hyaline

- Misfolded, aggregated and clumped intracellular cytoskeletal filaments due to alterations in the hepatocellular cytokeratin assembly, usually seen in ballooned hepatocytes and an indication of cellular injury

- Also referred to as Mallory-Denk body, alcoholic hyaline, intracytoplasmic hyaline

- Pathophysiologically, Mallory hyaline is formed due to the aberrant crosslinking, increased phosphorylation, partial proteolytic degradation and inadequate functioning of the normal ubiquitination of cytoskeletal proteins

- Commonly accumulate in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Wilson disease, cholestatic conditions (e.g. primary biliary cholangitis), following exposure to certain drugs like amiodarone, focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma

- On light microscopy, seen as irregular aggregates of clumped or ropy amorphous dense eosinophilic material in the cytoplasm most commonly in ballooned hepatocytes, sometimes forming a ring around the nucleus or surrounded by neutrophils

- Positive immunohistochemical and special stains: cytokeratin 8 / 18, ubiquitin, p62, stain blue with chromotrope aniline blue (CAB) special stain

- References: Med Mol Morphol 2010;43:13, Exp Cell Res 2007;313:2033, Hepatology 2007;46:851, J Pathol 1988;155:9, Virchows Arch 1998;432:143

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

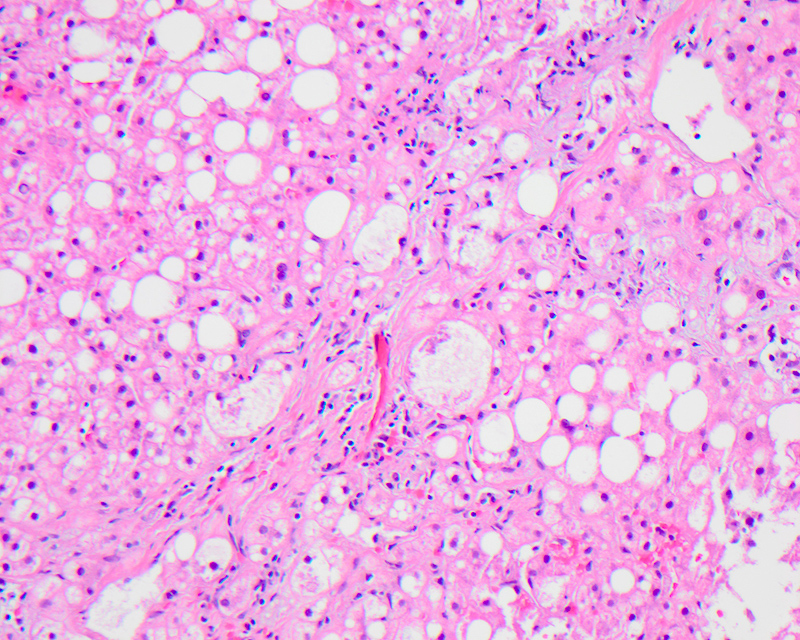

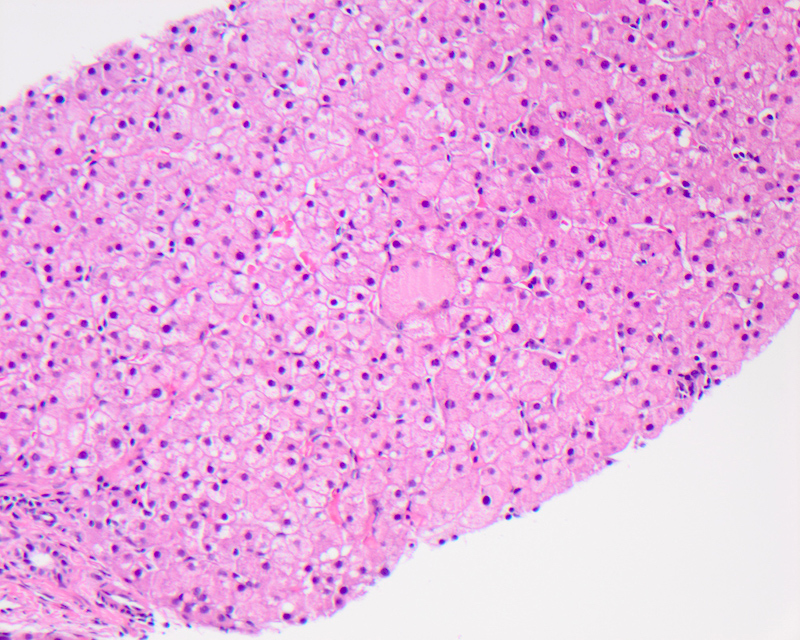

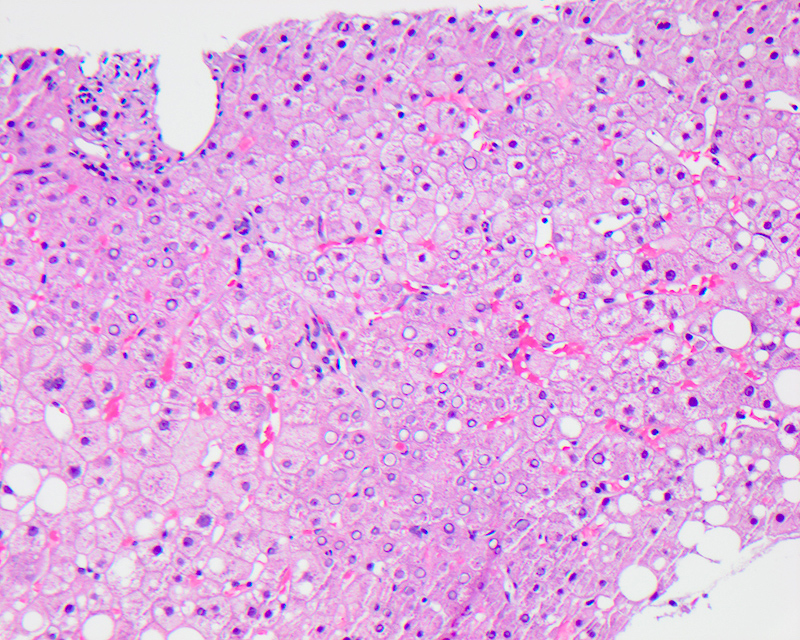

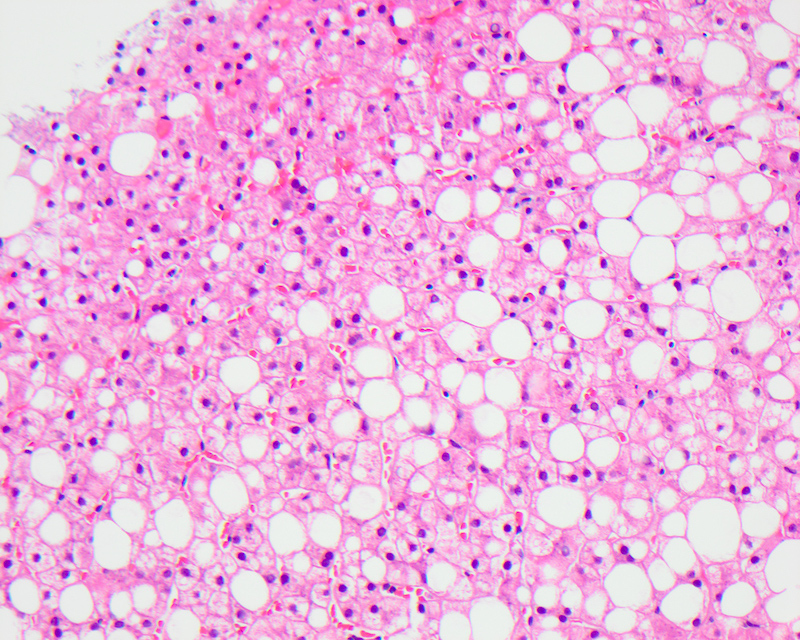

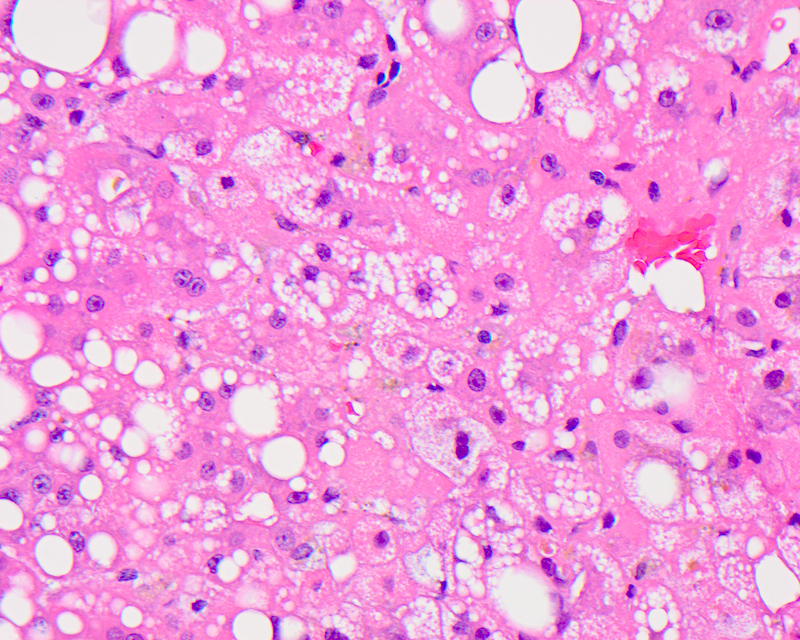

Macrovesicular steatosis

- Lipid filled hepatocytes with large fat droplets

- Radiographic modalities, including ultrasonography, magnetic resonance spectroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging, can detect fat in liver with high sensitivity and specificity; increased echogenicity of the liver, blurring of vascular margins and increased acoustic attenuation are features seen on ultrasound

- On gross examination, liver has a pale yellow appearance with greasy consistency; the color is due to retained carotenes

- Microscopically, usually large fat droplets are seen in hepatocytes (exceeding 20 micrometers), typically 1 per cell, pushing the nucleus to the periphery and giving an appearance of a signet ring / adipocyte; macrovesicular steatosis can be of the small droplet or large droplet type

- Seen in alcoholic or nonalcoholic liver disease and steatohepatitis, obesity, diabetes, chronic hepatitis C, protein calorie malnutrition, total parenteral nutrition, drugs effect (methotrexate or corticosteroids), Wilson disease

- More common than microvesicular steatosis

- Distribution of macrovesicular fat can be variable and seen in perivenular (centrilobular or acinar zone 3) zones in alcoholic steatosis and periportal areas or acinar zone 1 in wasting diseases like HIV / AIDS, severe protein calorie malnutrition and after corticosteroid therapy

- Grade of steatosis is usually reported based on the percentage of hepatocytes that contain lipid vacuoles:

- Minimal < 5% (essentially normal)

- Mild 6 - 33%

- Moderate 34 - 66%

- Severe > 67%

- Grading of steatosis has a major significance in evaluating liver transplant suitability of the donor and large droplet steatosis affecting > 30% of the liver graft hepatocytes is a poor prognostic indicator for graft survival in the recipient

- References: Radiology 2013;267:422, Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:168905, Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:686, Front Physiol 2019;10:429, StatPearls: Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver [Accessed 15 April 2021]

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

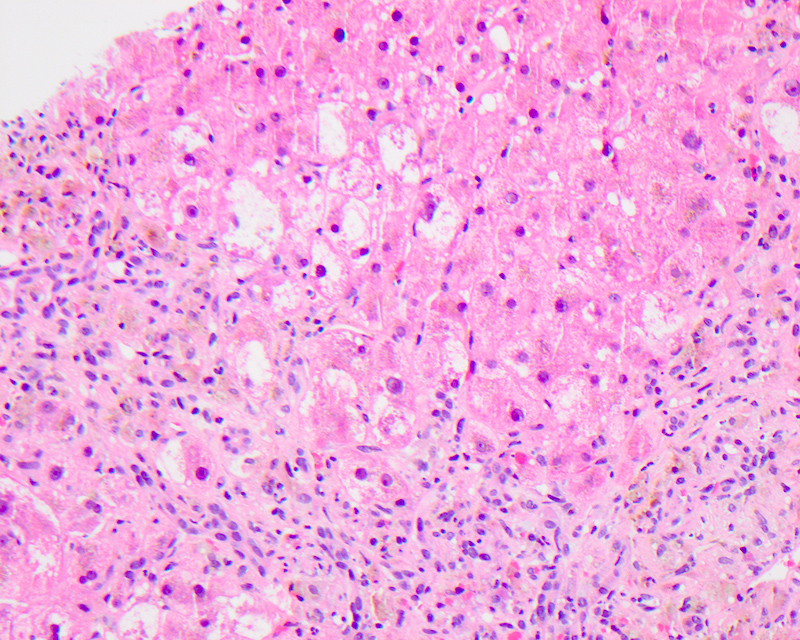

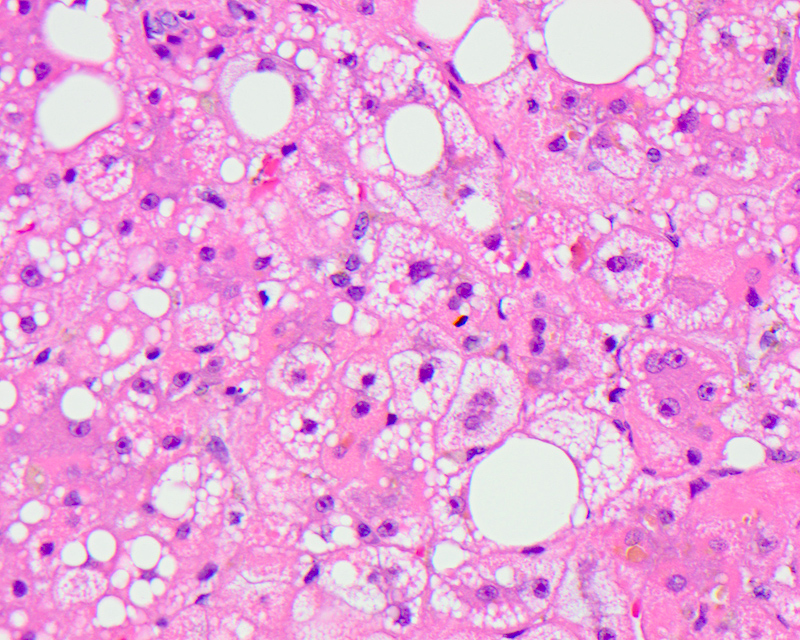

Microvesicular steatosis

- Lipid filled hepatocytes with innumerable small fat droplets around a centrally placed nucleus

- Diffuse microvesicular steatosis is considered a serious condition with hepatic dysfunction and coma

- Pathophysiologically, the development of microvesicular steatosis is thought to be secondary to impairment of beta oxidation due to inherited or acquired mitochondrial DNA mutations or deletions or direct inhibition of beta oxidation by drug metabolites in drug induced microvascular steatosis

- Microscopically seen as multiple tiny droplets (1 - 2 micrometers in diameter), imparting a foamy appearance to the cytoplasm that do not displace but can sometimes indent the nucleus; these numerous small droplets are sometimes barely visible at the resolution of light microscopy

- Seen in acute fatty liver of pregnancy, drug reactions like valproic acid, amiodarone and nucleoside analog toxicity, fatty acid β oxidation defects, Reye syndrome, mitochondrial DNA depletion and deletion syndromes, total parenteral nutrition, alcoholic foamy degeneration, inborn errors of metabolism disorders

- Pathologists sometimes disagree on interpretation of microvesicular steatosis vs. small droplet macrovesicular steatosis

- References: J Hepatol 2011;55:654, Acta Clin Belg 1990;45:311, Toxicol Pathol 2004;32:19

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

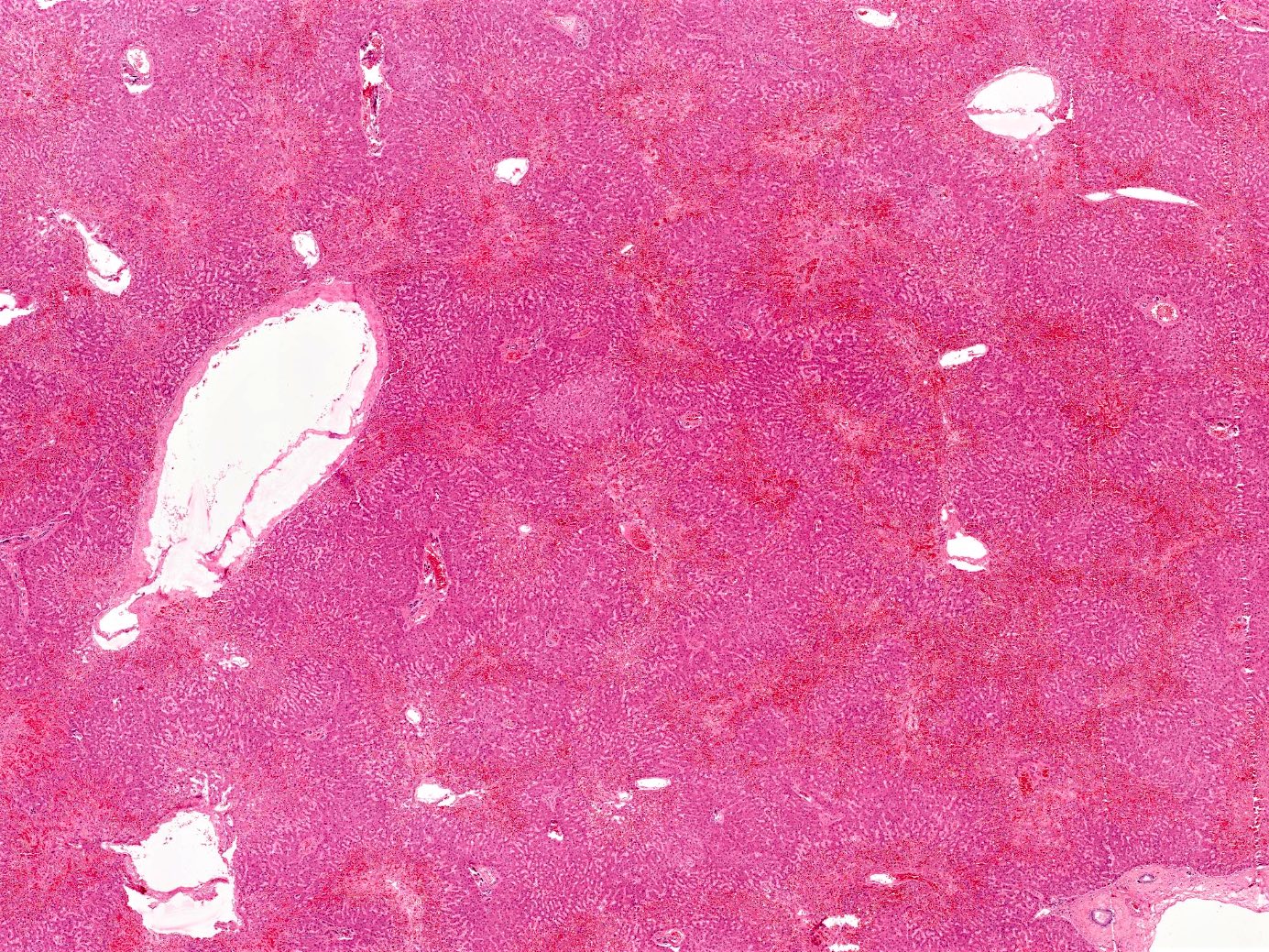

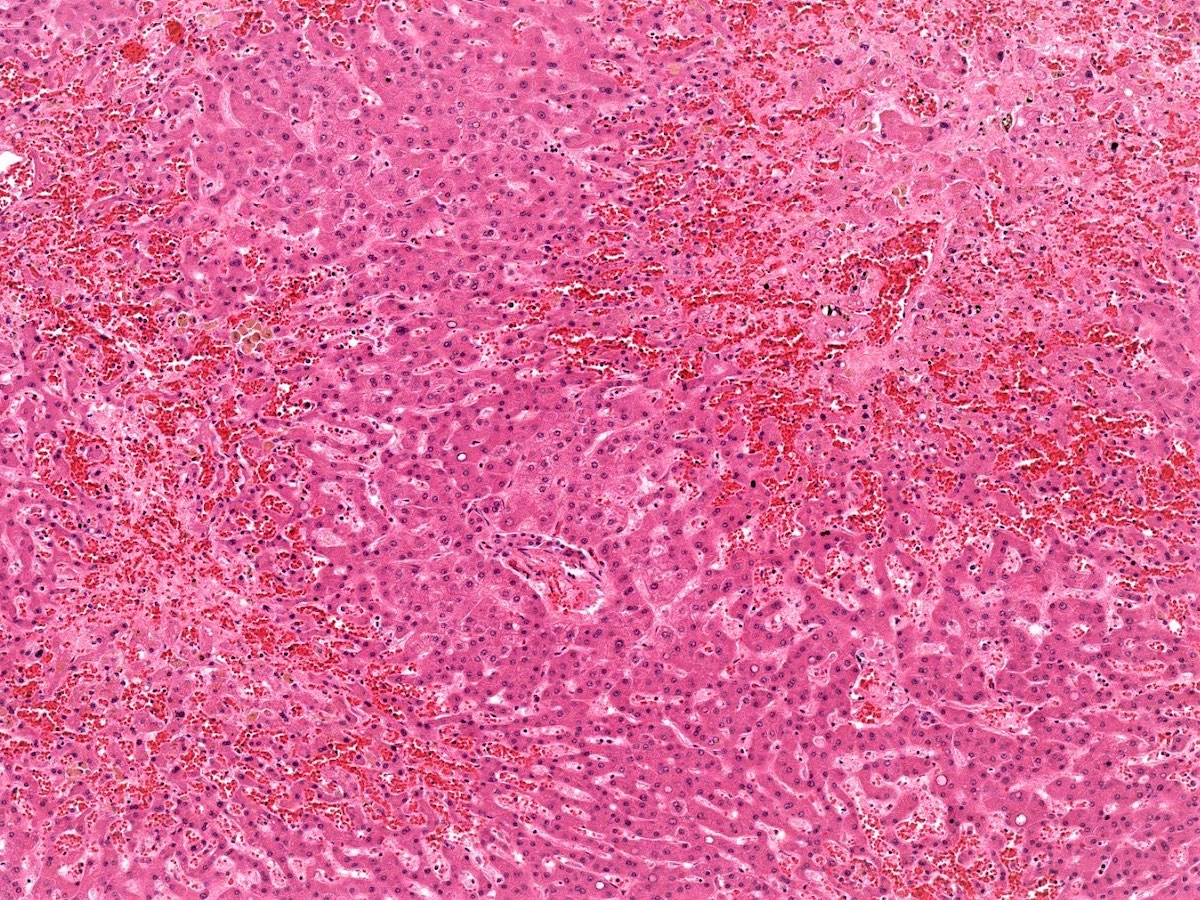

Passive congestion

- Acute liver injury to due to sudden, profound reduction in systemic blood flow

- Also referred to as acute hepatic ischemic necrosis, ischemic hepatitis, shock liver, hypoxic hepatitis, congestive hepatopathy, congested liver in cardiac disease

- Clinical findings are those of right sided heart failure, mild right upper quadrant abdominal pain (due to hepatomegaly and stretching of the hepatic Glisson capsule)

- Improvement of the hemodynamic status may result in rapid, dramatic hepatic response with normalization of serum transaminases within several days and complete recovery

- Pathophysiologically, stasis of blood in the hepatic parenchyma, due to impaired hepatic venous drainage, leads to the dilation of central hepatic veins and hepatomegaly; elevated hepatic venous pressure and decrease in hepatic venous flow causes hypoxic injury to hepatocytes and eventual diffuse hepatocyte death and fibrosis

- Most common causes of passive hepatic congestion are congestive heart failure, restrictive cardiomyopathy, constrictive pericarditis, right sided valvular disease involving the tricuspid or pulmonary valves, severe hypovolemia, septic shock, massive pulmonary embolism, hyperpyrexia, heat stroke

- 2 major commonly recognized histologic patterns of ischemic liver disease include centrilobular ischemic necrosis and hepatic infarction; these have the same basic pathophysiological process but differ in extent and distribution of hepatic damage

- On gross examination, the liver appears enlarged, firm and tender, with characteristic nutmeg appearance and darker zones representing the ischemic congested centrilobular areas alternating with pale areas

- Microscopic examination reveals perivenular sinusoidal congestion and increased pigment in the hepatocytes; prolonged cardiac failure can lead to liver cell necrosis and focal inflammatory infiltrates, as well as perivenular fibrosis extending to the portal tracts

- References: Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2017;10:49, Int J Angiol 2011;20:135

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

Images hosted on other servers:

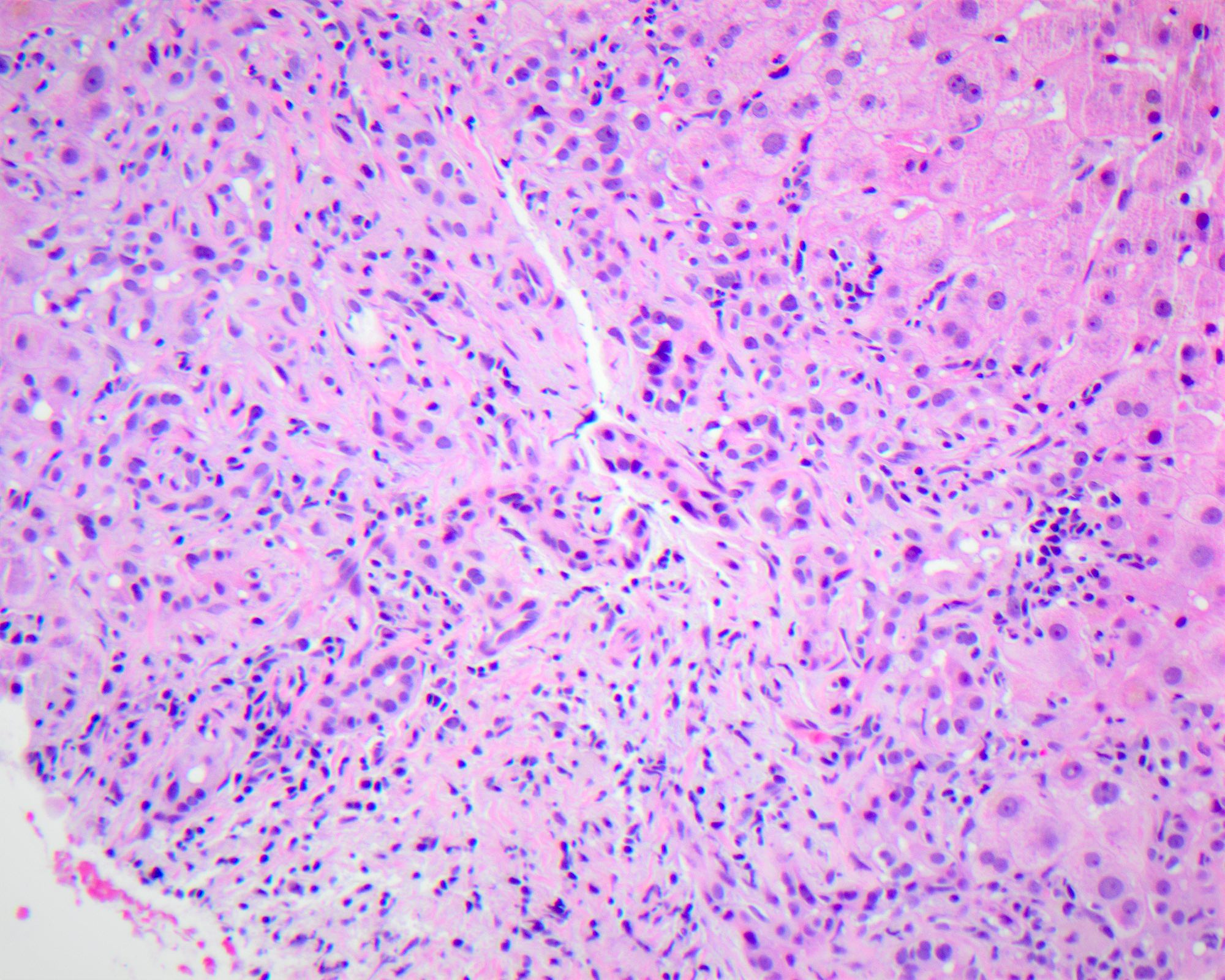

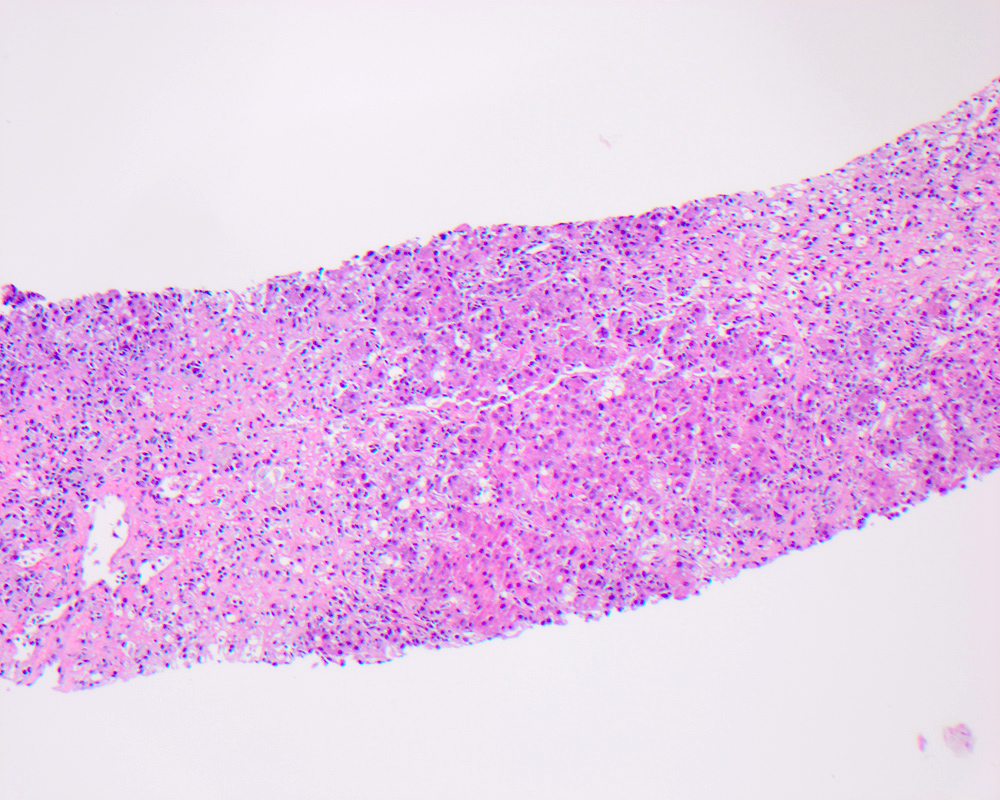

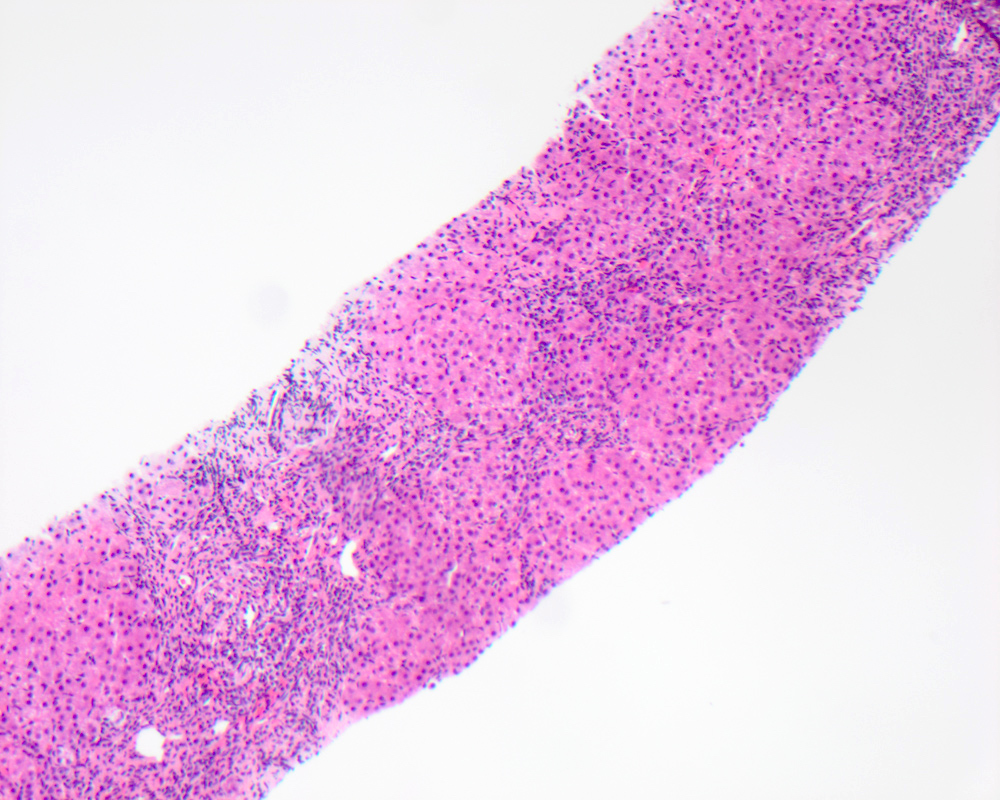

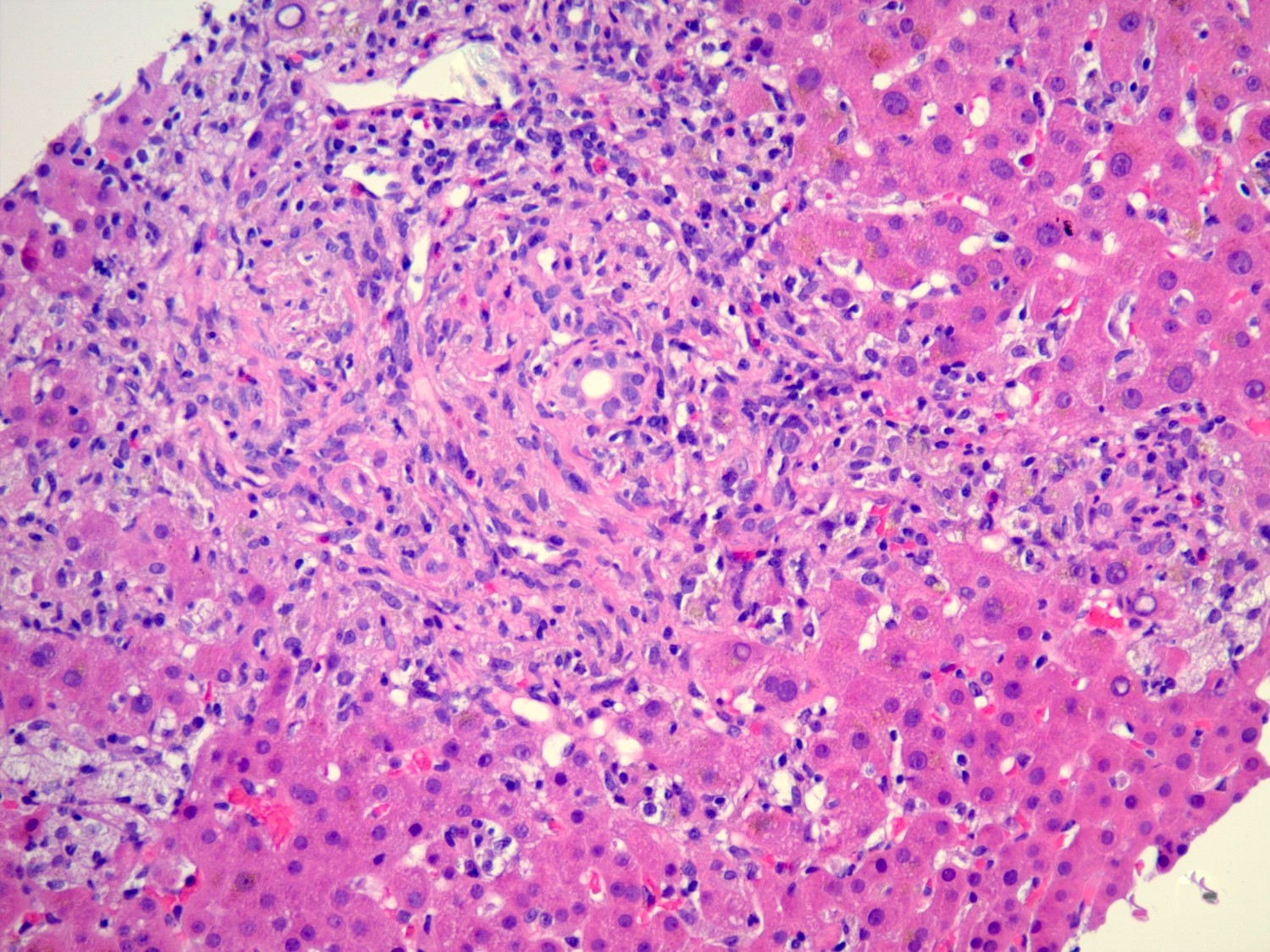

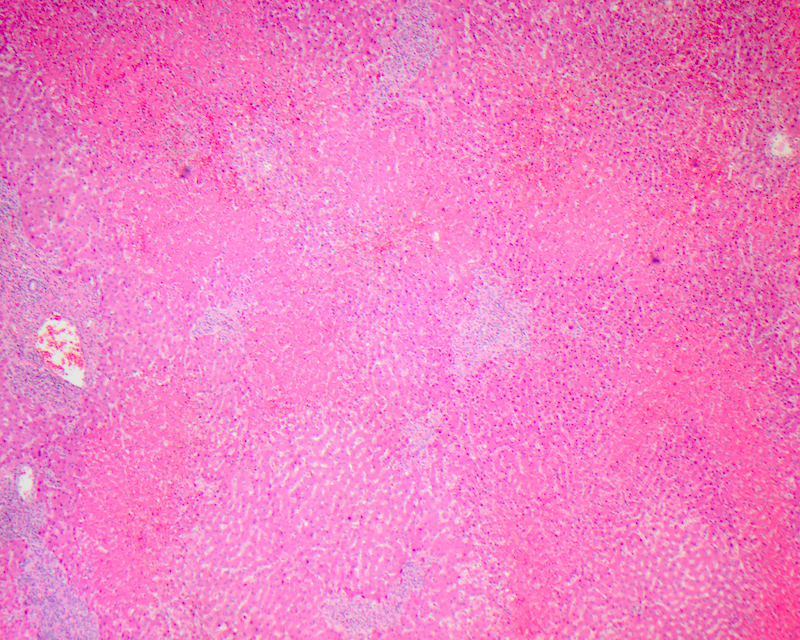

Submassive necrosis

- Refers to necrosis that affects a larger substantial area of hepatocytes rather than single cell programmed cell death

- Also referred to as confluent necrosis

- Most commonly seen in severe hepatitis, either due to viral, autoimmune or drug induced cases; in these conditions, necrosis is accompanied by an inflammatory reaction, usually associated with hepatic failure

- Less commonly, when submassive necrosis is seen in conditions leading to hypoperfusion of hepatic parenchyma, like shock, left ventricular failure, heatstroke or acetaminophen toxicity, it is accompanied by little or no inflammation

- May be zonal, involving a certain zone of the acini / lobule or nonzonal and random

- Confluent necrosis may bridge adjacent structures (bridging necrosis), extend over multiple lobules or acini (panlobular or panacinar necrosis) or extend over multiple lobules or acini (multilobular or multiacinar necrosis)

- In cases with submassive necrosis in which viable tissue remains, there is a striking proliferation of neocholangioles (bile ductules) as a reactive process, which over time, is followed by fibrous scarring

- References: Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2017;10:53, Acad Forensic Pathol 2018;8:256

Contributed by Krutika S. Patel, M.B.B.S., M.D. and Annika L. Windon, M.D.

Additional references

- Torbenson: Biopsy Interpretation of the Liver, 3rd Edition, 2014, Saxena: Practical Hepatic Pathology - A Diagnostic Approach, 1st Edition, 2011, Torbenson: Surgical Pathology of the Liver, 1st Edition, 2017, Burt: MacSween’s Pathology of the Liver, 7th Edition, 2017, Lefkowitch: Scheuer’s Liver Biopsy Interpretation, 9th Edition, 2015

Board review style question #1

Board review style answer #1

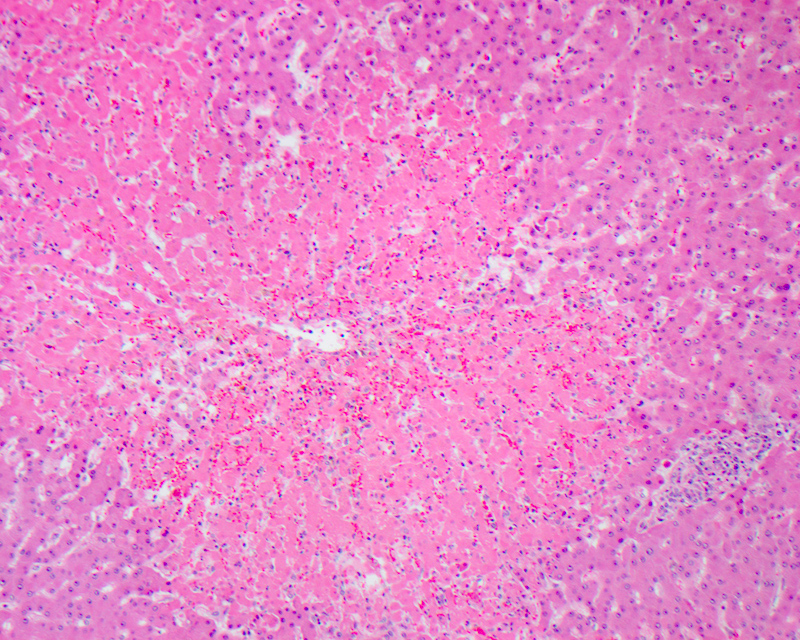

E. Ubiquitin. The image shows Mallory hyaline, seen as irregular aggregates of clumped dense eosinophilic material in the cytoplasm and representing misfolded, aggregated and clumped intracellular inclusions of intermediate cytokeratin due to alterations in the hepatocellular cytokeratin assembly, usually seen in ballooned hepatocytes. Mallory hyaline shows positive immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 8 / 18, ubiquitin and p62.

Comment Here

Reference: Forms of hepatic injury

Comment Here

Reference: Forms of hepatic injury

Board review style question #2

A predominant microvesicular pattern of steatosis is associated with

- Alcoholic steatohepatitis

- Corticosteroid therapy

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Reye syndrome

Board review style answer #2

E. Reye syndrome. Microvesicular steatosis is commonly seen in acute fatty liver of pregnancy, toxicity of drugs like valproic acid and nucleoside analogs, fatty acid beta oxidation defects, Reye syndrome, mitochondrial DNA depletion and deletion syndromes, total parenteral nutrition, alcoholic foamy degeneration and inborn errors of metabolism. Macrovesicular steatosis is commonly seen in alcoholic or nonalcoholic liver disease and steatohepatitis, obesity, diabetes, hepatitis C, protein calorie malnutrition, total parenteral nutrition and drugs like corticosteroids.

Comment Here

Reference: Forms of hepatic injury

Comment Here

Reference: Forms of hepatic injury